Part 4 of my Here-hood Saints series

Last year my family and I lived in the Summit Hill neighbourhood of Saint Paul. Specifically, we lived in an apartment complex that, for all intents and purposes, might have been in Mac-Groveland except that it sat on the eastern bank of Ayd Mill Road. East of us yet was the Roman Catholic Cathedral of Saint Paul. I have a habit of flipping the Cathedral an ironic, if heartfelt, salute every time we go past (which, the cathedral being located on the eastern end of University Avenue, we did often when we lived in Saint Paul). It was, after all, the seat and the great project of Archbishop John Ireland, who may be considered the originator of my church – the Orthodox Church in America.

The story of how the great reversion of Rusin immigrants into the Metropolia came about from the Archbishop’s rather impolitic behaviour to a certain immigrant priest is an infamous one these days, and it can be read in full elsewhere; suffice it to say that the troubles Rusins have historically had with ill-tempered Irish bosses does go back a rather long way. But our Bat’ko, Father Saint Alexis (Tovt), having been rebuffed by the local bishop here in the Twin Cities and threatened with being recalled to Austria-Hungary, went instead to the Russian bishop in San Francisco to be received into the Orthodox Church. Holy Father Alexis then went on to evangelise, bringing fifteen parishes with over twenty thousand Rusin-American immigrants back into the Orthodox Church. One of the churches Father Alexis founded was St. Mary’s Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Cathedral, pictured in my blog header. At Saint Herman’s on the Sunday of Orthodoxy I’ve made it a habit these past two years to bring my icon of Father Saint Alexis, which seems particularly fitting, given that he and his parish were baptised on that Sunday in 1891.

It’s a little weird living and going to church, as it were, at what is essentially ground zero for a mass conversion that transformed a large number of Greek-Catholic parishes into Orthodox ones over a relatively short period of time. Also, if on occasion I am hard on the Uniates (those of whom I’ve met locally being incredibly nice people), please understand that it is partly because ‘Minnesota nice’ can actually mask a lot of historical violence beneath the surface. The mass-reversion of the (mostly mine-working families) Rusin immigrants to Orthodoxy all along the Rust Belt is no exception to this rule. The conversion of Father Saint Alexis to Orthodoxy was not greeted meekly, tamely or peaceably – not by the Catholic hierarchy and certainly not by churchmen who remained in communion with Rome. It is instructive to read Father Alexis’s sermons and letters. In the immediate wake of the return of the Minnesotan (and Pennsylvanian) Rusin-Americans to Orthodoxy, there were a number of violent incidents. Threats were issued. Churches which reverted to Orthodoxy were vandalised – bricks thrown through windows, collection boxes robbed, a guard dog poisoned. Saint Alexis even survived an assassination attempt by a Uniate fanatic. At some point the Uniates realised that if Father Alexis Tovt was killed, it would make him a martyr for the cause of Orthodoxy in America, but they continued to attack the reverting Orthodox churches through the press, and through their coffers – a tactic which seems to have been at least partially effective. The letters of Father Alexis are filled with the prosaic and rather sad details of how his churches had to scrounge up paltry amounts of cash by selling off church goods and relying on support from San Francisco in order to meet court costs and legal fees.

In any event, the experiences of the working-class Rusin immigrants in these churches are not entirely gone. The old folk memory is there, particularly among the older laypeople in the parishes of the OCA and ACROD. It has been interesting to me to observe that the Rusin-Americans are insistent that they are not Ukrainian; they actually don’t mind being called ‘Slovaks’, but their sense of belonging – very much like that of the Jews who were their neighbours – is one that doesn’t fit neatly within nation-state boundaries. During the time of the migration across the Atlantic, the Rusin people were caught on the boundaries of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires. Before then, they had been robbed, enslaved, beaten and oppressed by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This folk history has been remembered in a fragmented way: stories handed down from the babushki about life in the old country; or habits kept out of fear of the police or of famine. One older Rusin-American friend of mine said she’d heard ‘Lemko’ (referring to a linguistic subdivision of the Rusin people) was used as a term of disparagement (this is something I couldn’t, in my limited knowledge, confirm or refute).

Just as some more radical Jews began in 19th century Russia and Poland to think of themselves as doyiker, the Ruthenian Orthodox peoples of the Commonwealth and the Monarchy were simply ‘tutešni’, which means the same thing: ‘people from here’. Their ‘here-hood’ was in part an imposition, but also in part stemmed from an unwillingness to form a political-linguistic identity which fit into the ideological boxes provided to them by their colonial masters. To be ‘tutešni’ is to be neither ‘Ukrainian’ nor ‘Russian’ nor ‘Hungarian’ nor ‘Slovak’ nor ‘Polish’.

The ecclesiastical-political orientation of the mission of Father Saint Alexis Tovt among the Rusins was accused of having a ‘Russophile’ or ‘Moscophile’ flavour by his enemies in the streets, in the courtroom and in the press. The Rusins who ‘went over’ – or ‘perekhodyty’, in the polemical language of the Uniate press – to Orthodoxy were accused of being a potentially-traitorous fifth column for Russia, a charge which was opportunistically credited on account of their involvement in labour disputes. (Sound familiar?) Indeed, he speaks of these accusations specifically in his sermons, and attempts to hold out for a surprisingly nuanced position. On the one hand, he commemorates the Russian Tsar as a patron of his church. Further, he speaks of the need for his people – whether they call themselves Slovaks or Russians – to demonstrate material kindness and brotherly solidarity to other immigrants in America, particularly those from other Slavic countries. On the other hand, he encouraged his parish to learn English, not to drink or party to excess, to attend public schools and to support the labour movement. There were two sides to his civic thinking; even if he didn’t embrace assimilation with both arms, neither did he give in to an implicit anarchism or allow himself to be cowed by his detractors into a reactive stance. Being the ‘people from here’ who are also self-consciously migrants (physically, civilly, religiously) is a tenuous position indeed.

There are several other noteworthy parallels I could – and will eventually – mention between the Moravian Jewish family connexions I seem to keep coming back to, and the Rusin(-American) experience. However, the (self-?) designation as ‘tutešni’ and its parallel with the ‘doyiker’ idea in contemporary Jewry is simply too good to ignore in connexion with the careful position that Holy Father Alexis had to stake out in his public priestly mission, which was all the more tenuous for his and his parishes’ chronic poverty.

In the meantime, being a fragmented and recently-Minneapolitan Orthodox Christian convert of Czech extraction and walking a path that intersects this folkway at a number of different points, I will simply ask: Holy Father Alexis, pray to God for me, a sinner.

26 July 2018

Venerable Moses Ugrin of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra

Saint Moses of Kiev, whom we commemorate today, is one of three brothers, who all hailed from the Carpathian Mountains, who all served in the retinue of Saint Boris the Martyr-Prince of Rostov, and who all met salvific ends in Christ – but who did so along very divergent paths.

Saint Yuri of Al’ta, the youngest brother, was slain and beheaded alongside Saint Boris when the latter yielded himself without struggle into the murderous hands of his brother Svyatopolk. Venerable Efrem of Novotorzhsk was not with Saint Boris at the time, but later found Saint Yuri’s remains and buried his body before retiring from the world, leaving instructions to his fellow-monks to bury his brother’s head alongside him. The third brother, Saint Moses, had a rather more eventful life. Moses escaped the clutches of Svyatopolk and fled to Kiev where he sought refuge with the sister of Yaroslav the Wise. However, when the city was captured by the Polish King Bolesław, he was taken prisoner-of-war and made a slave.

A Polish noblewoman, seeing Moses’ tall and handsome shape and conceiving a deep lust for him, bought him, unwilling, from Bolesław and sought to make him her bed-thrall. She tempted him with her body; however, Moses refused her advances. She plied him with all sorts of delicious food, but he would not eat it. She then took him in an open carriage and showed him all of the wealthy lands of which she was mistress; however, Moses was bent upon becoming a monk, and told her that the perishable wealth of the world could not tempt him.

A mendicant monk who happened to be passing through tonsured Moses. When his Polish owner found out about it, she became furious and ordered Moses to be flung onto the ground and beaten with heavy iron rods until the ground was soaking with his blood. Then, she sought Bolesław’s permission to do with him as she pleased, and he gave her this right. She then forced him into bed with her and tried, unsuccessfully, to rape him. Frustrated and humiliated, the Polish noblewoman ordered him to be beaten every day 100 times with the lash until he bled to death.

On account of this defiance, Bolesław planned to undertake a great persecution of monks in the Polish lands, but his death prevented this order from being carried out. The Polish noblewoman was killed in a peasant uprising shortly thereafter. As for Moses himself, he escaped once again – but he had been so badly wounded and crippled from the tortures he had undergone that he had to lean on a staff whenever he walked. He made his way to the Kiev Pechersk Lavra where he took the cowl.

Saint Moses lived for ten years at the Lavra under the tutelage of Holy Father Antoniy, and was a firm support to his fellow monks there. One brother approached him, confessing that he had lustful thoughts. Moses sought the brother’s obedience, and forbade him to speak to any woman as long as he lived. Then he struck the brother on the chest with his staff, and at once the brother was relieved of his temptations. The Venerable Moses reposed in the Lord in 1043.

Venerable Moses of Kiev, for the deliverance of all slaves from their captivity, for the deliverance of us all from the passions and for the salvation of our souls, pray to Christ our God for us sinners!

25 July 2018

Back to the good earth

The 1931 novel The Good Earth by Pearl S Buck has a well-deserved place on my list of books that changed my life – because it, along with the Judge Dee murder mysteries by Robert van Gulik, stoked in me an abiding interest in the history and lifeways of old China. Having recently looked into the works of Jimmy Yen 晏陽初, Liang Shuming 梁漱溟, Tao Xingzhi 陶行知 and Richard Tawney, then having understood that Pearl Buck herself was not only a contemporary but a friend and fellow-traveller of this literary-political-activist circle that would become the China Democratic League, I felt it high time I went back and read this touchstone of my high-school years.

It’s funny: perspective changes radically with age and distance. Different aspects of the story came to the surface, reading through The Good Earth this time, than when I was, well, half my current age. The story itself was familiar. Poor, hard-working Wang Lung, living alone with his fussy and aged father, takes a wife from the Great House of Hwang – a plain, seemingly dull-witted but intensely loyal and surprisingly-profound serving-girl named O-lan. Together Wang Lung and O-lan make a life for themselves: planting and harvesting, having children, being forced to move by famine, being forced to move again by revolution. Wang Lung experiences both the bitterest deprivations – losing his home and having to live on his hands and on whatever O-lan and his children can beg – and later the temptations and vices of wealth, as his fortunes improve and he comes into possession of more and more of the land of the House of Hwang.

Certain things I noticed in the story that I didn’t before – the geographical features and the importance of, not only earth, but water as an elemental force in the lives of Chinese peasants – with small surfeits or dearths either way being deadly. The attention paid to the labour-intensive agricultural techniques. A subtle but persistent sexism which is as often expressed in the actions of the women in the story (Old Mistress Hwang, Cuckoo, Lotus, even occasionally O-lan herself) as those of the men. There is a great wealth of knowledge of Chinese folkways at the grassroots which breaks forth from the pages, which is clearly the fruit of close observation. The selective folk-piety of the peasant, easily discarded or inverted. The fear and distrust of soldiers. The paranoia of the wealthy that their money and goods will be stolen. These are just a handful of examples.

Again, the story, the characters, the struggles and conflicts between them were all deeply familiar to me from my high-school years, and this time experience lay over it, giving my mental pictures some greater depth. In one sense, reading it now gave me a new appreciation for Buck’s authorial talent, being able to inhabit and express the perspectives of people in wildly different walks of life – in a culture not her own. That’s something I admire and value. On the other hand, certain stylistic choices and choices of characterisation she makes – for instance, the character of Cuckoo, who seems to take on three different personæ (lord’s mistress, tea-shop madam, lady-in-waiting) as the story demands it – seem a trifle questionable, and the reasons for her ‘switching hats’ so often seem rather ad hoc. Still, the treatment of Cuckoo – and O-lan, Lotus and Pear Blossom, the women in Wang Lung’s life – is meant to show how, even for a good-natured and generally ‘well-behaved’ husband like Wang Lung, women still ended up getting a raw deal in China’s old society. O-lan, faithful but slow and not particularly pretty, is treated by her husband like a piece of furniture. Wang Lung chases Lotus, a prostitute who becomes his second wife, but when she enters the household she treats Wang Lung’s first wife and daughters with open contempt. (We get intimations that her childhood was also deeply unhappy.) Pear Blossom grows up as a servant in Wang Lung’s household, in deadly fear and loathing of young men in particular – and little wonder, given how she sees how Wang Lung’s sons and nephew treat the womenfolk. On the other hand, Buck’s portrait of Wang Lung’s relationship with his eldest daughter, a ‘poor fool’ with a mental disability, is truly touching: probably this is a reflection of her relationship with her own daughter, who also had a developmental disability.

Again, being a bit more familiar now with Pearl Buck’s literary milieu I searched the book for signs of her politics and religious sensibilities, only to find that – talented an author as she is! – she hides her tracks well. Her characterisation of a communist radical preaching on the street, and Wang Lung’s interested-but-incredulous reaction to him, provides a little bit of intellectual comedy. The radical scoffs at Wang Lung as ‘backwards’, but Wang Lung’s perspective that real wealth comes from the topsoil is presented sympathetically. Wang wonders how it happens that the bourgeoisie can prevent the sun from shining or the rain from falling. And although we are left to infer rather than having it spelt out for us directly, Buck’s sympathies with the peasantry in general, we see perhaps traces of her antipathy to both foreign political concepts and missionary Protestant Christianity in the fact that O-lan makes shoe linings out of their pamphlets, though this is as much to show O-lan’s thrift and practicality during their sojourn in the ‘south’ as anything else.

Speaking of which, Buck does present a certain set of gæographical biases and stereotypes, of the sort which Jimmy Yen did his best to refute and combat. ‘Northerners’ like O-lan (from Shandong) and Wang Lung (from Anhui) are simple, thrifty, hard-working – noble even in their poverty and direct even when begging or stealing. ‘Southerners’ like Cuckoo and Lotus are subtle, crafty, able to work the angles. She presents, I think, several of the ways in which discrimination has historically tended to operate (for example, with ‘southerners’ looking down on ‘smelly’ garlic-eating northerners). It’s actually still a bit unclear to me, whether she presents these stereotypes because she believes them to be accurate, or whether she is attempting (as with her treatment of the various women in her story, and their struggles) to prompt an internal critique of them.

The foregoing might make it sound like I want to pick The Good Earth apart, but really – far from it! This novel is both the sprawling epic of one man’s very full and varied life, and a touchingly-intimate, if somewhat dated, portrait of a ‘China that was’. Buck is very rightly regarded as an author of the first calibre for this book in particular, and it was a joy to go back and revisit this novel, which has dwelt deep so long in my memory and on my bookshelf.

20 July 2018

The hiraeth (and exhortations) of the expat

Part 3 of my Here-hood Saints series

Life as an expat can be very difficult, and it shapes you in ways that you would not have imagined beforehand. My wife and I have both lived as expats. There is a kind of ‘weightlessness’ with it, which is spoken of by Mother Maria of Paris, whose memory we celebrate today alongside her fellow new martyrs Saints Il’ya (Fondaminsky), Dimitri (Klepinin) and Yuri (Skobtsov). The expat is cut loose from the bonds that tether him: the exhortations of his elders, the expectations of his peers. The new society which surrounds him has not lain hold of him yet. Mother Maria perceived this perfectly when she said that losing one’s homeland is something akin to losing one’s body – though in her case, the trauma was doubled by the fact that her expat displacement was political and involuntary.

When you’re an expat, after that initial glow of the ‘honeymoon stage’ of living in a wondrous new place wears off, you begin to draw close to ‘your own’. You seek out people who are like you, who speak the same language, who share the same outlook. In both cities I lived in, Baotou and Luoyang, my closest friends were young Englishmen with an interest in video games: we bonded over Europa Universalis 3 and Super Smash Bros. If you’re not careful, the weightlessness becomes that of a fragile but impermeable soap-bubble, and you can develop all manner of bad habits and vices. But if you keep your experience permeable, there is also an opportunity for a ‘double witness’ in the expat life. (I’m afraid I’ve only become semi-good at one of the directions of that witness – and vices, I developed too many.)

Another saint with an icon at Saint Herman’s which, like Saint John of Shanghai and San Francisco’s, I had often venerated without knowing precisely why I do it, is that of Patriarch Saint Tikhon of Moscow. Like with Saint John, I’ve been mesmerised by his face. Examine the icon of Saint Tikhon. His white brows and intense eyes, although they have a fierce, almost burning kindness, nonetheless express themselves with a certain kind of sadness, a look of what the elder Britons would call hiraeth. It’s a look I’ve seen often in the faces of expats. Before I read his letters, before I knew his story, I venerated him simply because it seemed he knew what it was to be weightless.

Of course, knowing his story as I do now, it seems somewhat that that hiraeth would have been for the loss of the Russia he knew to the ideological war zone that took its place after 1917, and not perhaps so much that from his time in the Americas. He became, not merely an expat, but an exile within his own nation. But it doesn’t take a great stretch of the imagination to think on what it would have been to him, to serve as the archpastor among a people so alien to him as we Americans are. The Orthodox of the Americas were, even in his day, a motley crew, a mishmash of poor immigrants from around the globe. (It seems I can’t help myself, making these hard rock and heavy metal references with regard to the history of our church. Of course Tommy Lee is a Greek; but that’s an excuse, not an explanation.)

Bishop Tikhon – suddenly servant not only to Russian-Americans but also to Rusins, South Slavs, Syrians, Inuits and Aleuts – could very well have retreated to his bubble, and kept to his bishop’s office in Alaska or New York. But he didn’t. The weightlessness of being an expat led him instead to a new intensity of witness, and he spent much of his American sojourn in travel. In his correspondence, we can see how he responded to the sufferings of the Aleuts to famine and sickness: he issued ringing clarion calls to their aid and denounced the attitudes of racial superiority that kept them in poverty. Seeing Rusin, Serbian, Montenegrin and Bulgarian mine workers beleaguered and striking to fill their bellies, he gave from his own money to support them, and told his flock to do the same. He financially and spiritually supported Father Alexis (Tovt) in his mission to his fellow Rusins. Seeing Syrians in need, he blessed the Church of Saint Nicholas in Brooklyn for them.

Bishop Tikhon bore his witness by keeping his attention on where he was. Even as an expat, even untethered from his Russian home country, even constantly in travel, even beset – we may easily imagine – by that intense sadness and longing for home, Bishop Tikhon was here, with the Orthodox who had come to the New World from many other shores. Even thus ‘weightless’, he could still give of his own substance for his flock who needed him, and he did so. There was a kind of doyikayt, a ‘here-hood’ even in his life abroad.

My wife’s politics are a good deal more conservative, in the conventional American sense, than mine are. There are a set of typical attitudes that prevail among immigrants in the United States, and she seems to have imbibed many of these, such as: success is the result of effort and intelligence; and those who gain by success have a right to keep it. She has a deep antipathy to affirmative action, which she sees – with some justification, it appears – as a form of discrimination against Asians. She also has next to no patience for the internal ‘identity politics’ of Asian-Americans. Her conviction is that Asian-American groups – including not just Chinese-Americans but also Japanese-, Korean-, Hmong-, Lao- and Vietnamese-Americans – need to work together and put aside their differences rather than keeping to their own separate ethnic enclaves.

But even in the ‘weightlessness’ of life as an expat, she hasn’t lost a deep sense of compassion and solidarity. I’ve seen it repeatedly, and it’s one of the things I fell in love with about her. She made personal connexions with her fellow foreign students in Pittsburgh and was more than willing to help them with either school-related or life problems when they arose. Most recently, upon hearing the news about family separations at the border, she told me bluntly: caring for these people is America’s responsibility. It should be part of our character. There’s more than a little bit of Saint Tikhon’s expat sensibility in my wife’s thinking and manner of expression, and I continue to be endeared to it.

Now, of course, I venerate Saint Tikhon at church not merely for that face – compassionate, fierce, joyful and sad all at once, the face of an expat. There was a great deal of dynamism in that holiness, as I learned from his writings – some of which were even addressed to us Minnesotans, the spiritual children of Holy Father Alexis, and all of which we can still learn from. Saintly Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow, continue to pray to God for me, a sinner.

Life as an expat can be very difficult, and it shapes you in ways that you would not have imagined beforehand. My wife and I have both lived as expats. There is a kind of ‘weightlessness’ with it, which is spoken of by Mother Maria of Paris, whose memory we celebrate today alongside her fellow new martyrs Saints Il’ya (Fondaminsky), Dimitri (Klepinin) and Yuri (Skobtsov). The expat is cut loose from the bonds that tether him: the exhortations of his elders, the expectations of his peers. The new society which surrounds him has not lain hold of him yet. Mother Maria perceived this perfectly when she said that losing one’s homeland is something akin to losing one’s body – though in her case, the trauma was doubled by the fact that her expat displacement was political and involuntary.

When you’re an expat, after that initial glow of the ‘honeymoon stage’ of living in a wondrous new place wears off, you begin to draw close to ‘your own’. You seek out people who are like you, who speak the same language, who share the same outlook. In both cities I lived in, Baotou and Luoyang, my closest friends were young Englishmen with an interest in video games: we bonded over Europa Universalis 3 and Super Smash Bros. If you’re not careful, the weightlessness becomes that of a fragile but impermeable soap-bubble, and you can develop all manner of bad habits and vices. But if you keep your experience permeable, there is also an opportunity for a ‘double witness’ in the expat life. (I’m afraid I’ve only become semi-good at one of the directions of that witness – and vices, I developed too many.)

Another saint with an icon at Saint Herman’s which, like Saint John of Shanghai and San Francisco’s, I had often venerated without knowing precisely why I do it, is that of Patriarch Saint Tikhon of Moscow. Like with Saint John, I’ve been mesmerised by his face. Examine the icon of Saint Tikhon. His white brows and intense eyes, although they have a fierce, almost burning kindness, nonetheless express themselves with a certain kind of sadness, a look of what the elder Britons would call hiraeth. It’s a look I’ve seen often in the faces of expats. Before I read his letters, before I knew his story, I venerated him simply because it seemed he knew what it was to be weightless.

Of course, knowing his story as I do now, it seems somewhat that that hiraeth would have been for the loss of the Russia he knew to the ideological war zone that took its place after 1917, and not perhaps so much that from his time in the Americas. He became, not merely an expat, but an exile within his own nation. But it doesn’t take a great stretch of the imagination to think on what it would have been to him, to serve as the archpastor among a people so alien to him as we Americans are. The Orthodox of the Americas were, even in his day, a motley crew, a mishmash of poor immigrants from around the globe. (It seems I can’t help myself, making these hard rock and heavy metal references with regard to the history of our church. Of course Tommy Lee is a Greek; but that’s an excuse, not an explanation.)

Bishop Tikhon – suddenly servant not only to Russian-Americans but also to Rusins, South Slavs, Syrians, Inuits and Aleuts – could very well have retreated to his bubble, and kept to his bishop’s office in Alaska or New York. But he didn’t. The weightlessness of being an expat led him instead to a new intensity of witness, and he spent much of his American sojourn in travel. In his correspondence, we can see how he responded to the sufferings of the Aleuts to famine and sickness: he issued ringing clarion calls to their aid and denounced the attitudes of racial superiority that kept them in poverty. Seeing Rusin, Serbian, Montenegrin and Bulgarian mine workers beleaguered and striking to fill their bellies, he gave from his own money to support them, and told his flock to do the same. He financially and spiritually supported Father Alexis (Tovt) in his mission to his fellow Rusins. Seeing Syrians in need, he blessed the Church of Saint Nicholas in Brooklyn for them.

Bishop Tikhon bore his witness by keeping his attention on where he was. Even as an expat, even untethered from his Russian home country, even constantly in travel, even beset – we may easily imagine – by that intense sadness and longing for home, Bishop Tikhon was here, with the Orthodox who had come to the New World from many other shores. Even thus ‘weightless’, he could still give of his own substance for his flock who needed him, and he did so. There was a kind of doyikayt, a ‘here-hood’ even in his life abroad.

My wife’s politics are a good deal more conservative, in the conventional American sense, than mine are. There are a set of typical attitudes that prevail among immigrants in the United States, and she seems to have imbibed many of these, such as: success is the result of effort and intelligence; and those who gain by success have a right to keep it. She has a deep antipathy to affirmative action, which she sees – with some justification, it appears – as a form of discrimination against Asians. She also has next to no patience for the internal ‘identity politics’ of Asian-Americans. Her conviction is that Asian-American groups – including not just Chinese-Americans but also Japanese-, Korean-, Hmong-, Lao- and Vietnamese-Americans – need to work together and put aside their differences rather than keeping to their own separate ethnic enclaves.

But even in the ‘weightlessness’ of life as an expat, she hasn’t lost a deep sense of compassion and solidarity. I’ve seen it repeatedly, and it’s one of the things I fell in love with about her. She made personal connexions with her fellow foreign students in Pittsburgh and was more than willing to help them with either school-related or life problems when they arose. Most recently, upon hearing the news about family separations at the border, she told me bluntly: caring for these people is America’s responsibility. It should be part of our character. There’s more than a little bit of Saint Tikhon’s expat sensibility in my wife’s thinking and manner of expression, and I continue to be endeared to it.

Now, of course, I venerate Saint Tikhon at church not merely for that face – compassionate, fierce, joyful and sad all at once, the face of an expat. There was a great deal of dynamism in that holiness, as I learned from his writings – some of which were even addressed to us Minnesotans, the spiritual children of Holy Father Alexis, and all of which we can still learn from. Saintly Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow, continue to pray to God for me, a sinner.

18 July 2018

Holy New Martyr Elizaveta Fyodorovna

Today we commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the political murder of another of the Romanovs, Martyr Elizaveta Fyodorovna of Moscow, born Princess Elizabeth of Hesse-Darmstadt, the older sister of Tsarina Aleksandra whose memory we celebrated yesterday. A Lutheran German noblewoman who converted to Orthodoxy upon marrying her husband, she took to her new faith with the same passion, or even a greater one, than she brought to her marriage. Her husband, the Grand Duke Sergei, was killed by a member of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party to which belonged also, ironically, the New Martyr of Paris, Mother Maria (Skobtsova). She forgave her husband’s murderer, urged him to repent and even asked for his sentence to be commuted.

She became a true ‘social justice’ saint, and her life seems to have taken a parallel track to that of Mother Maria of Paris: after her husband’s death she sold everything she had, became a nun, started a convent, and founded within the convent grounds a hospital and an orphanage, and went outside herself to serve the poor and the sick of Moscow. Holy New Martyr Elizaveta thus stands in the great Constantinian Byzantine tradition of philanthrōpia, as well as in the peculiarly Muscovite tradition of caritative kenoticism. Even as she was dying, having been thrown down an old mineshaft by her Bolshevik killers, her very last Christ-like acts were to bandage the wounds of those within reach of her. She bore witness to Christ in the very truest sense of the word.

(As a minor point of interest, her relics seem to have been borne by the Whites to China and spent some time in Beijing in the care of the Russian mission there. They did not remain, however, as Saint John’s did.)

The Life of New Martyr Elizaveta Fyodorovna is recounted here by the Orthodox Church in America:

Saint Elizabeth was the older sister of Tsarina Alexandra, and was married to the Grand Duke Sergius, the governor of Moscow. She converted to Orthodoxy from Protestantism of her own free will, and organized women from all levels of society to help the soldiers at the front and in the hospitals.Holy Martyr Elizaveta Fyodorovna, pray to God for us sinners!

Grand Duke Sergius was killed by an assassin’s bomb on February 4, 1905, just as Saint Elizabeth was leaving for her workshops. Remarkably, she visited her husband’s killer in prison and urged him to repent.

After this, she began to withdraw from her former social life. She devoted herself to the Convent of Saints Martha and Mary, a community of nuns which focused on worshiping God and also helping the poor. She moved out of the palace into a building she purchased on Ordinka. Women from the nobility, and also from the common people, were attracted to the convent.

Saint Elizabeth nursed sick and wounded soldiers in the hospitals and on the battle front. On Pascha of 1918, the Communists ordered her to leave Moscow, and join the royal family near Ekaterinburg. She left with a novice, Sister Barbara, and an escort of Latvian guards.

After arriving in Ekaterinburg, Saint Elizabeth was denied access to the Tsar’s family. She was placed in a convent, where she was warmly received by the sisters.

At the end of May Saint Elizabeth was moved to nearby Alopaevsk with the Grand Dukes Sergius, John, and Constantine, and the young Count Vladimir Paley. They were all housed in a schoolhouse on the edge of town. Saint Elizabeth was under guard, but was permitted to go to church and work in the garden.

On the night of July 5, they were all taken to a place twelve miles from Alopaevsk, and executed. The Grand Duke Sergius was shot, but the others were thrown down a mineshaft, then grenades were tossed after them. Saint Elizabeth lived for several hours, and could be heard singing hymns.

Emulating the Lord’s self-abasement on the earth,

You gave up royal mansions to serve the poor and disdained,

Overflowing with compassion for the suffering.

And taking up a martyr’s cross,

In your meekness you perfected the Saviour’s image within yourself,

Therefore, with Barbara, entreat Him to save us all,

O wise Elizabeth.

17 July 2018

Centenary of the Royal Passion-Bearers

One hundred years ago today, the lives of seven members of the Russian royal family – Tsar Nikolai II, his wife Aleksandra, and their five children Olga, Tatyana, Maria, Anastasia and Aleksei were murdered by the Bolsheviks, along with their servants. All of the members of the royal family are accounted as saints today by the Russian Church (although their status as martyrs is still slightly disputed). In addition, a number of the murdered servants of the royal saints of Russia were canonised: Evgeny Botkin; Aloysius von Trupp; Ivan Kharitonov; Anna Demidova; Anastasia Hendrikova and Catherine Schneider. A good historical case can be made, that the murder of the royal family and their servants marked definitively the beginning of the twentieth century and its attendant ideologically-driven evils.

Whether one calls him a passion-bearer or a martyr, though, the memory of the murdered Tsar is therefore important, not only to the Rodina and not only to the Russians in diaspora, but to the Orthodox Christians on the North American continent as well. The commemoration of the saintly Tsar and his family is not simply a ‘Russian thing’.

One highly noteworthy thing about Tsar Nikolai II, in life and in death, is how driven practically all of the contemporary North American saints of what was then the Metropolia (now the OCA) were driven to defend him both personally and politically. They all seem to have been impressed by his genuine goodwill and his robust and active support of the Church in its North American mission. Father Saint Alexis (Tovt) publicly commemorated the Tsar among his working-class Rusin congregants. Patriarch Saint Tikhon (Bellavin) was a defender, both of Nikolai II and of his office, being particularly cognisant of the unpopularity of both in American culture. Bishop Saint Raphael (Hawaweeny) served the Syrian Arab community – at the time consisting mostly of poor street pedlars and wage-workers – in New York at the Tsar’s personal request; his bishop’s robes were a gift from the autocrat himself. Archbishop Saint John (Maksimovich) gave a stirring sermon rousing the Russian people to repentance on the fortieth anniversary of the Tsar’s abdication.

Devotion to the Tsar among Russian and Rusin Orthodox Christians in America in particular is quite noteworthy. Fr Peter (Kohanik), a Rusin priest from Bekheriv (in the Bardejov District in current-day Slovakia) said this about the Tsar, quoting a few passages from another sermon delivered by the pastor of the Broadway Tabernacle in New York:

Study the face of Nicholas II, Czar of Russia. It is not the face of a warrior. It is the face, rather, of an artist or a poet. Remember that it was he who, first impressed by the arguments of Jean de Bloch, called the first Hague Conference, some fifteen years ago, hoping that the nations might agree on a reduction in armaments. Read his telegram to his cousin, the King of England, in which he declared that he had done everything in his power to avert the war. Surely this is not a man who wanted to deluge Europe in blood, or who is to be held responsible for what is going on in Europe.Even one hundred years on, Tsar Nikolai’s place in history is still ‘up for grabs’. Indeed, as Romanovs go, Tsar Nikolai II hearkened back in a number of ways to the first of his royal line, Mikhail I, who was elected to office by the zemsky sobor of 1613 – or indeed, before Mikhail, to the Royal Passion-Bearers Boris and Gleb. Like Mikhail, Tsar Saint Nikolai II was meek, gentle, kindly and self-effacing in public, and his devotion to the Church only served to accentuate this mild character. Like Mikhail, Nikolai II did accept the responsibilities of the Tsardom, but with great reluctance. And like Mikhail, Nikolai II took the throne at a ‘time of troubles’: the difference, however, was that the troubles which afflicted Mikhail were largely external (invasions from Poland and Sweden), and the troubles afflicting the reign of Nikolai II were largely internal. His reign was plagued by internal problems from the very beginning, but he insisted on sharing in the pains of his people. He personally visited those injured in the Khodynka tragedy; during the Great War he went himself to the front, to be present with the troops who were suffering and dying in his allegiance.

The biased critic will sneer at this, of course, and say there was a motive for him in proposing the universal peace, but it was ever thus—one can’t please everybody!

Russia is still coming to grips with its own history. Russians under Soviet rule had been taught to despise the last tsar as a cruel and unfeeling tyrant, but even this ‘official’ line of ham-fisted propaganda had started to come under revisionist scrutiny while the Soviet Union was still standing. Even as early as Brezhnev’s leadership, Soviet historians began to portray Nikolai II with a greater degree of sympathy – although their opposition to the Tsarist system was still absolute. Today, the popular caricature of Nikolai II that still holds some currency – and which is, in some ways, more insidious – is that of Nikolai II as an inept, dithering weakling, hen-pecked by his shrewish wife and brought down by his poor judgement and his reliance on malicious and self-seeking charlatans like Grigory Rasputin.

This caricature is not of Soviet origin; it owes its existence instead to liberal-conservative ‘White’ historiography. It can be traced to the popular English-language histories of Russia written by George Vernadsky (whose liberal-conservative politics can be traced to the Kadet party) and Nicolas Riasanovsky (a scholarly zapadnik whose political views can be characterised as ‘liberal nationalist’). Vernadsky and Riasanovsky did not set out to defame the Tsar, of course. But ultimately a large portion of the pop-cultural image of the royal family owes itself to their work. That work did all possible to accentuate their political tendency’s contributions in the post-1905 ‘constitutional’ era, and to downplay the positive contributions the Tsar himself had to the same period. The beneficial aspects of the reforms of Russian society under Tsar Nikolai II were to be attributed to advisers like Sergei Witte and Pyotr Stolypin, whereas the failures were to be laid at the feet of the Tsar himself. And these ‘Whites’ bore the typical resentment of the Russian nobility against the German ‘foreigner’ Aleksandra, whose very closeness to the seat of political power and her support for autocracy engendered suspicion and misogynistic speculation about her relationship to the Tsar. We must not forget that the Kadets were no true friends of the Tsar, and their bile has had a longer shelf-life than that of the Bolsheviks.

According to KH King, the Tsar was neither coldly aloof from public life nor was he ignorant of its demands. Going from archival accounts and drawing from a broad array of historical data, she shows that Tsar Nikolai II had a personal hand in bringing about, not only in the Hague Peace Conference referenced above by Fr Peter (Kohanik), but also in the industrial modernisations, the Factory Law of 1897 mandating a maximum 10-hour workday, the 1905 Treaty of Portsmouth ending the war with Japan, the post-1907 land reforms and the public health insurance system of 1912. His sum-total impact on Russian public life simply was not one of ineptitude and indifference, still less one of cruelty; many of the reforms that he not only put pen to but supported or originated. It will not do to politically ‘rationalise’ the death of the Tsar, or to make of it a vulgar kind of morality play for ideological purposes. The Tsar was, all-around, a good and kind man who stood in the way, and was killed for it.

Regarding Nikolai II’s personal life, there is of course nothing in the historical record to indicate that he was anything other than a devoted family man, or that his relationship with the Tsarina Aleksandra was anything less than loving, even passionate. He doted on his children, and the only reason Grigory Rasputin was allowed anywhere near the family lay in Tsar Nikolai’s belief that his faith could heal his hæmophiliac son.

The last of the Russian Tsars and his family were the victims of cruel, brutal, senseless politically-motivated violence at the hands of the Bolsheviks. It cannot be emphasised enough, however, how much both the ‘Red’ and the ‘White’ ideological contortions of the history of the last Tsar must be overcome, for the repentance that Saint John (Maksimovich) called for to be completely embraced. And this repentance is not only for the Russian people, but for those of us in other nations who have been touched by his generosity and example, and who are still (as evidenced by the incivility and bad manners of our elected leadership) hostile to the very concept of civic monarchism. One hundred years on – let us try to learn, in some small degree, the lessons of this tragic history. Holy Royal Passion-Bearers Nikolai, Aleksandra, Olga, Tatyana, Maria, Anastasia, Aleksei – pray to God for us sinners!

Most noble and sublime was your life and death, O Sovereigns;

Wise Nicholas and blest Alexandra, we praise you,

Acclaiming your piety, meekness, faith, and humility,

Whereby you attained to crowns of glory in Christ our God,

With your five renowned and godly children of blessed fame.

O passion-bearers decked in purple, intercede for us.

13 July 2018

A practical peasant martyr-monk

Part 2 of my Here-hood Saints series

I was received into the Holy Orthodox Church by chrismation on 17 February 2014, by Fr Sergiy Voronin, the rector of Holy Dormition Church in Beijing. Fr Sergiy asked me before I was chrismated there if there was anyone I wanted to have witness the ceremony – I wanted two of my friends from Beijing to be there, but unfortunately both of them were out of town that day. When I was chrismated, then, it was just me, Fr Sergiy and an empty sanctuary. But: no Orthodox sanctuary is ever truly empty; the Father, Christ and the Holy Spirit are all very much present there. In addition, there truly was someone witnessing my chrismation that day, though his presence was at that time unbeknownst to me. At the foot of the altar before which I was anointed and before which I made my profession of faith and renunciation of the Evil One, there lay the relics of Saint John (Pommers) of Riga.

I’ve suffered from convertitis myself, and quite badly, as I’ve explained before (and likely demonstrated, on this same blog). But if I’ve been spared the excesses of it at all, I feel as though that would be owing to the prayers of my priests, and also to Saint John’s prayers. Saint John was, after all, a steady and level-headed Latvian peasant. As a young man he herded sheep, and worked on his parents’ farm during the summers even after he started going to school. He loved the Church – what hagiography of a saint of the Russian Church would say otherwise? – but he always had his eye on what was close at hand: he was doyiker (after my ‘spiritual’ usage of the word). He attended to the needs of his parents, and he lived a very frugal and practical life. He kept an eye on local public matters: he advocated for literacy and sobriety among the peasants, helped the unemployed, and worked as a peasant organiser even as he began his monastic life.

And he found himself being drawn into politics. He was ordained a bishop by Patriarch Saint Tikhon (Bellavin), with whom he had a close and friendly relationship, and regardless of where he went he gained the trust of the common people, both the peasants and the workers. He didn’t hesitate to speak on their behalf, and he was willing to do the hard grassroots work, building labour unions among the peasantry. Most of Latvia’s Orthodox population were, in fact, poor peasants who had been landless. In the late 1830’s there was a great mass conversion of Latvian peasants and agricultural labourers to the Orthodox Church, and most of these peasants belonged to the lowest rung of the ladder. The Pommers family to which Saint John belonged, however, had been Orthodox long before that.

After Latvia gained its independence and the Latvian Orthodox Church was granted a certain degree of autonomy, Saint John joined the Saeima (the Latvian Parliament) representing an Orthodox populist party together with his Russian colleague, teacher and labour unionist EM Tikhonitsky. The programme of the Party of the Orthodox may sound familiar: land reform and peasant self-organisation; mass education and literacy; religious and cultural rights for Latvia’s Russian minority. Though it broadly fit into the agrarian politics of interwar Eastern Europe, the Party of the Orthodox didn’t map neatly into the contemporary political landscape. Latvian left-wingers distrusted Saint John of Riga as a Tsarist; rightists distrusted him as a peasant rabble-rouser. Ultimately, in all likelihood, it was a Soviet agent who killed him on account of his political efforts.

Saint John’s holiness has a certain worldly quality – I say that meaning, ‘free from illusions’. Again, I don’t trust coincidences in the church – I don’t think it was an accident, therefore, that Fr Sergiy gave me as a baptismal gift the book Everyday Saints by Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov). Saint John was not a typical monk, not a typical bishop – he had been a hard-working and practical peasant, a filial son and an activist in his sæcular life, and he remained very much himself even as he became a monk and a bishop later in life. There are many kinds of holiness. Each must choose to carry her own cross. Sudden transformations of spirit are not the universal rule. If I came to realise that in any fragmentary form, backing away from a rigid hyperdox zealotry, again I wonder if I oughtn’t to attribute that to the prayers and efforts of Fr Sergiy and Saint John of Riga alongside him. The martyr of Riga, his relics at rest in a small Chinese mission church, was here, at my baptism; he is here still.

Holy New Hieromartyr John, I know you’ve been praying for me these past four and a half years, and I thank you. Pray for me still, an unworthy sinner, and bless my hands and heart to the work before me.

I was received into the Holy Orthodox Church by chrismation on 17 February 2014, by Fr Sergiy Voronin, the rector of Holy Dormition Church in Beijing. Fr Sergiy asked me before I was chrismated there if there was anyone I wanted to have witness the ceremony – I wanted two of my friends from Beijing to be there, but unfortunately both of them were out of town that day. When I was chrismated, then, it was just me, Fr Sergiy and an empty sanctuary. But: no Orthodox sanctuary is ever truly empty; the Father, Christ and the Holy Spirit are all very much present there. In addition, there truly was someone witnessing my chrismation that day, though his presence was at that time unbeknownst to me. At the foot of the altar before which I was anointed and before which I made my profession of faith and renunciation of the Evil One, there lay the relics of Saint John (Pommers) of Riga.

I’ve suffered from convertitis myself, and quite badly, as I’ve explained before (and likely demonstrated, on this same blog). But if I’ve been spared the excesses of it at all, I feel as though that would be owing to the prayers of my priests, and also to Saint John’s prayers. Saint John was, after all, a steady and level-headed Latvian peasant. As a young man he herded sheep, and worked on his parents’ farm during the summers even after he started going to school. He loved the Church – what hagiography of a saint of the Russian Church would say otherwise? – but he always had his eye on what was close at hand: he was doyiker (after my ‘spiritual’ usage of the word). He attended to the needs of his parents, and he lived a very frugal and practical life. He kept an eye on local public matters: he advocated for literacy and sobriety among the peasants, helped the unemployed, and worked as a peasant organiser even as he began his monastic life.

And he found himself being drawn into politics. He was ordained a bishop by Patriarch Saint Tikhon (Bellavin), with whom he had a close and friendly relationship, and regardless of where he went he gained the trust of the common people, both the peasants and the workers. He didn’t hesitate to speak on their behalf, and he was willing to do the hard grassroots work, building labour unions among the peasantry. Most of Latvia’s Orthodox population were, in fact, poor peasants who had been landless. In the late 1830’s there was a great mass conversion of Latvian peasants and agricultural labourers to the Orthodox Church, and most of these peasants belonged to the lowest rung of the ladder. The Pommers family to which Saint John belonged, however, had been Orthodox long before that.

After Latvia gained its independence and the Latvian Orthodox Church was granted a certain degree of autonomy, Saint John joined the Saeima (the Latvian Parliament) representing an Orthodox populist party together with his Russian colleague, teacher and labour unionist EM Tikhonitsky. The programme of the Party of the Orthodox may sound familiar: land reform and peasant self-organisation; mass education and literacy; religious and cultural rights for Latvia’s Russian minority. Though it broadly fit into the agrarian politics of interwar Eastern Europe, the Party of the Orthodox didn’t map neatly into the contemporary political landscape. Latvian left-wingers distrusted Saint John of Riga as a Tsarist; rightists distrusted him as a peasant rabble-rouser. Ultimately, in all likelihood, it was a Soviet agent who killed him on account of his political efforts.

Saint John’s holiness has a certain worldly quality – I say that meaning, ‘free from illusions’. Again, I don’t trust coincidences in the church – I don’t think it was an accident, therefore, that Fr Sergiy gave me as a baptismal gift the book Everyday Saints by Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov). Saint John was not a typical monk, not a typical bishop – he had been a hard-working and practical peasant, a filial son and an activist in his sæcular life, and he remained very much himself even as he became a monk and a bishop later in life. There are many kinds of holiness. Each must choose to carry her own cross. Sudden transformations of spirit are not the universal rule. If I came to realise that in any fragmentary form, backing away from a rigid hyperdox zealotry, again I wonder if I oughtn’t to attribute that to the prayers and efforts of Fr Sergiy and Saint John of Riga alongside him. The martyr of Riga, his relics at rest in a small Chinese mission church, was here, at my baptism; he is here still.

Holy New Hieromartyr John, I know you’ve been praying for me these past four and a half years, and I thank you. Pray for me still, an unworthy sinner, and bless my hands and heart to the work before me.

11 July 2018

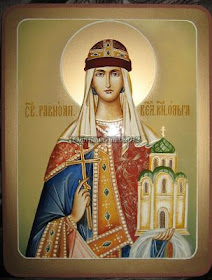

Heilaga Helga inn fagra, Jafn við Postulana

Saint Olga of Kiev, Equal to the Apostles, has a privileged and – in my view – admirable place in the sanctuary of Saint Herman’s. A Scandinavian saint of the Orthodox Church, standing alongside Saint Moses the Black and Saint Herman the Wonderworker of Alaska, her presence and juxtaposition seem to offer a gentle, subtle rebuke to those in the Church who would promote certain racialist political agendas. Saint Moses the Black, of course, had been a slave and a bandit who later turned to the monastic life; Saint Herman was a missionary monk among the natives of Alaska and a fervent advocate for their rights and dignity comparable to Bartolomé de las Casas among the Spanish. I don’t know if this placement of Saint Olga alongside Saints Moses and Herman at our parish was planned or a deliberate choice, but I do not trust coincidences, particularly not in the church.

There are other factors which make such a placement appropriate. Saint Olga – likely named Helga in the Norse – was born in the countryside around Pskov (then Pleskov) to an East Norse Varangian noble family in the Izborsk lineage, and married in her youth to Ívarr of Kœnugarðr (Kiev). At this time, the Rus’ polity was still pagan, and Ívarr had to deal with the problems typical of a tribal Norse leader in the midst of Slavic pagan peoples. The tributary Slavic nation, the Drevlyane, had stopped paying the tribute to Ívarr’s predecessors, and Ívarr himself was determined to restore the relationship. He went to Korosten’ to collect tribute from the Drevlyane, who – not being impressed by Ívarr’s ouvertures – lynched him in a grisly way: by stringing him up between two bent birch saplings and then letting the saplings go, tearing him apart.

The Drevlyane expected Ívarr’s widow to be meek and easily cowed. Their prince, Mal, offered to marry her and seal the alliance that Ívarr had sought to restore – on terms favourable to them. Olga, receiving the Drevlyan prince’s twenty heralds, had them all buried alive under their own boats. She then sent a messenger of her own, pretending to accept Mal’s proposal and asking that she be given an escort of Drevlyan noblemen suitable to her status as the lady of Kœnugarðr. Mal sent his best men to retrieve her. She sent them to wash off in the sauna, but then had the doors barred and the sauna set alight, burning the entire Drevlyane escort to death inside.

She then went herself to Korosten’, to mourn her husband’s death before she would wed Mal, and arranged a large banquet to be held. Despite not having heard back from either party of their messengers, the Drevlyane feasted and got themselves drunk at the banquet, and when they were all intoxicated, she ordered the men she had brought with her to put them all to the sword – five thousand Drevlyane were thus gruesomely dispatched.

This was still not the end of her bloody vengeance on behalf of her murdered husband, though. Her armies laid waste to the lands of the Drevlyane, until they had to beg her to make peace on them, offering her furs and honey if she would only stop attacking them. Seeming to soften, the Primary Chronicle notes, she asked:

Give me three pigeons and three sparrows from each house. I do not desire to impose a heavy tribute, like my husband, but I require only this small gift from you, for you are impoverished by the siege.The Drevlyane complied. What Helga did with this tribute of live fowl is the stuff Icelandic sagas are made of.

Now Olga gave to each soldier in her army a pigeon or a sparrow, and ordered them to attach by thread to each pigeon and sparrow a piece of sulphur bound with small pieces of cloth. When night fell, Olga bade her soldiers release the pigeons and the sparrows. So the birds flew to their nests, the pigeons to their cotes, and the sparrows under the eaves. The dove-cotes, the coops, the porches, and the haymows were set on fire.The fearsome destruction and the insatiable fury wreaked by the widowed Helga, as described in the Tale of Bygone Years, has been glossed thus by our hagiographers:

There was not a house that was not consumed, and it was impossible to extinguish the flames, because all the houses caught on fire at once. The people fled from the city, and Olga ordered her soldiers to catch them. Thus she took the city and burned it, and captured the elders of the city. Some of the other captives she killed, while some she gave to others as slaves to her followers. The remnant she left to pay tribute.

Having sworn their oaths on their swords and believing “only in their swords”, the pagans were doomed by the judgment of God to also perish by the sword (Mt. 26: 52). Worshipping fire among the other primal elements, they found their own doom in the fire. And the Lord chose Olga to fulfill the fiery chastisement.As a pagan, Olga gained still greater reputation as a skilful manager in peacetime, establishing a system of pogosti across the lands of the Rus’ which served as legal courts and administrative centres for the collection of tribute. However, she did not remain a pagan long after this. Very much like her grandson, the saintly Valdimárr Sveinaldsson (Prince Vladimir of Kiev), baptism into the Orthodox Church seems to have truly transfigured her. Even though, as one of the first of the Rus’ to be baptised into the Christian faith, she was immediately embroiled in civil and religious struggles with her pagan kin and vassals, she would never again use the kind of ruthless tactics of war she had deployed against the Drevlyane. Instead, she sought to exercise influence through moral suasion. In the case of her son Svenald Ívarsson (or Svyatoslav Igorevich), she did not succeed. However, she managed to keep a firm hold over her grandson’s upbringing, which no doubt influenced his ultimate decision to become baptised an Orthodox Christian himself – along with his entire revenue, at Korsun’.

This kind of transfiguration – with her will and personality intact, but her vengeful and violent tendencies transmuted into the peaceable weapons of faith – very closely mirrors the life and spiritual trajectory of Saint Moses the Black: another reason why I think the juxtaposition of these two icons is so apposite. Saint Moses began his life as a slave, who committed a murder and joined a band of robbers in the Wâdi al-Natrun. As he was physically the strongest and temperamentally the most ruthless of these bandits, he quickly made himself their leader, and committed numerous acts of butchery and banditry in this life. Suddenly and unaccountably, though, Saint Moses was taken with remorse, and begged to be admitted to the monastic life of the hermits in the wâdi. This sudden transformation and acceptance of Christianity deeply influenced Moses’ character; although he lost none of his physical strength and none of his strength of will, he practised a demanding form of self-abnegation. He refused to pass judgement even on his brothers who committed faults.

There were other facets to this baptismal transfiguration in Saint Olga’s case. Saint Olga of Kiev also turned her formidable administrative talents after her conversion from the collection of tribute to the establishment of hospitals and the distribution of food and necessities to the poor. Though she did this mostly on an individual basis as the mother and regent of the king of Kœnugarðr, this kind of public philanthrōpia would later become a bedrock of Rus’ social ethics when the entire polity became Christian. For this reason among many others, we truly call upon Saint Olga as an ‘equal-to-the-apostles’. She did most of the heavy labour of bringing Christianity to the Russian world; whether in her personal witness, in her public comportment, or in the raising of her grandson. Saint Olga, Right-Believing Princess of Russia, pray to God for us!

Giving your mind the wings of divine understanding,

You soared above visible creation seeking God the Creator of all.

When you had found Him, you received rebirth through baptism.

As one who enjoys the Tree of Life,

You remain eternally incorrupt, ever-glorious Olga!

10 July 2018

Russophobia as orientalism

Well, the Wall Street Journal cover story this week, with the artwork featured above, is something truly awful. But, even an awful picture can be worth a thousand words. As The People’s Lobby’s Tobita Chow put it in his Facebook comment on the story: ‘On the bright side, this saves me the trouble of having to make a bunch of careful arguments to show that Russia has been Orientalised.’

I have indeed tried to make such careful arguments a few times before, though I have had to fight explicitly against the likes of the old racialist dreck of the Marquis de Custine being peddled about behind the convenient shield of Czesław Miłosz (and if I were feeling particularly uncharitable, I could link de Custine’s dreck explicitly to that of Arthur de Gobineau; they stand firmly in the same tradition). But this recent bit of overt old-school orientalism from the Wall Street Journal does indeed make my job significantly easier. News Corporation has grown significantly more bald-faced with such things of late. Even though cable-news ‘personality’ Tucker Carlson seems to have a soft spot for Russia, his tirades against China tap into some Gilded Age neuroses about the Yellow Peril, and Trofimov’s piece linking Putin’s Russia to Shyńǵys Khan links up with that neatly.

This line of discourse in Western thought goes back much further than Custine, of course. The orientalist dichotomy between a virtuous republican West and a decadent despotic East was central to the thinking of Machiavelli, Smith, Montesquieu and Mill, and it exerted a significant influence as well over Hegel, as well as Marx at certain stages of his career, though the Marx of die Grundrisse was noticeably more sympathetic to Asia in general than the Marx of das Kapital. The question of whether non-Western Europeans are capable of philosophy is one which has had a shamefully long life, spanning from Kant to Derrida (and Žižek).

But this question becomes much more complex (well, maybe not much more) where Russia is concerned, in part because ‘Russia’ – and here I include all of Kievan Rus’, the principalities of Rostov-Suzdal-Vladimir, Novgorod, Pskov, Tver, Polotsk, the Tsardom of Moscow, the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union as well as the modern Russophone lands – is a contested space where civilisations collide; Russian thinkers and artists been both the authors and the self-aware objects of orientalist fantasy. There has long been a tension between those Russians who face ‘West’ and those who face ‘East’; the result is that some ‘Eurasian’ thinkers, such as the martyred Saint Il’ya (Fondaminsky-Bunakov), have approached the question of where Russia belongs in stunningly creative and multifaceted ways.

Sadly, this entire history of engagement, and its fruits, are sent into oblivion with ‘a stereotype, wrapped in a cliché, inside a caricature’. The Wall Street Journal plays into a long-standing genre in the Western press (and more broadly into the Custine-Gobineau tradition of polemical literature) portraying Russians as ‘barbarians from the East’: Tatars, Mongols and Turks bent on bloody conquest for reasons inscrutable to more civilised (Western) minds – and, in Trofimov’s breathless hyperbole, constitutes a threat to the ‘very concept of the West’ itself! (Of course Aleksandr Dugin gets name-dropped here, despite being a marginal figure at best in Russian public life.)

One has to understand that Trofimov is not arguing from a neutral perspective. He is a Ukrainian ‘liberal’ nationalist, and writes from a historiographical perspective indebted to Mikhail Hrushevsky. Hrushevsky was a far better ideologue than a historian; his aim was to create an ideological space for a Westward-looking Ukraine that could distinguish itself from Russia, and the existing orientalist mythos was a tool ready to hand. Though Hrushevsky himself may or may not have been an anti-Asian racist (as alleged by Sergei Samuilov among others), his assertion of a ‘rupture’ between a Kievan Rus’ belonging to Europe and a Rostov-Suzdal-Vladimir belonging to Asia absolutely did borrow heavily from Machiavellian orientalist fantasy, and certainly did set the stage for later racialist theorising about the Asiatic Mongol-Turkic-Ugric heritage of ‘Muscovy’ which renders it alien to that of Kievan Rus’. Actual history tends to be slightly more complicated. But here’s the real kicker. Trofimov spent much of his life outside the West, as a reporter on Middle East politics and current affairs. Familiar as he is with the ‘near East’ and its history, there is no way he is repeating these orientalist canards about Russia without an understanding of the ideology he is reproducing, which is what makes the Wall Street Journal piece more galling even than the laughably ign’ant screeds which make the rounds on Euromaidan Press.

Of course, as mentioned above, this entire discourse is made further complex by the fact that there exists a strong tendency within Russia and the diaspora to embrace the East, to override the ‘me/them’ dichotomy and replace it with something like a ‘we’. Dugin is far from the only, and far from the most interesting or sympathetic, of the thinkers representing this tendency. I mentioned Saint Il’ya (Fondaminsky) already; his compatriots Mother Maria (Skobtsova) and Nikolai Berdyaev were in some degree also influential here. The idea of an as-yet-incomplete creative synthesis of West and East held resonance with several thinkers in the Russian diaspora and within Russia itself. It remains influential, but it’s not a threat save to those to whom the radicalism of Christianity itself is already a threat.

05 July 2018

Where we live, there is our land

Part 1 of my Here-hood Saints series

I am an amnesiac. I am an American. The two go together, and not altogether on account of the alliteration. And it would go together with being a son of Adam, for that matter – poor bloke got tricked into eating a fruit and forgot what good and evil were. My amnesia gives me a double mind; it is not the cause of my guilt, but I am guilty of it anyway. Věra Danzer Cooper – the Jewish grandmother I never knew, and never knew I had until high school – has been something of a haunting presence in my life: more so than I would have thought possible at the time. The sweet and smiling face in the yellowed photographs, almost the double of my younger sister’s, somehow ‘clicked’ something in my mind. Separated as we were by generations (but not by gæography, she also a Wisconsin girl planted in Rhode Island!), she made certain abstractions concrete. She sparked in me a fascination with genealogy, which in turn led me to discover certain rhymes and patterns in my own family life. Blood is thicker than water. Water evaporates. Blood leaves marks and scars. Both flowed from the side of Christ, pierced by a Roman spear at the behest of my kin. Tertullian talked about the ‘blood of the saints’ as the ‘seed of the Church’. There’s a truth in that, but we’ll get to it later.

Blood links me indelibly to Wisconsin and to Rhode Island – both of them my childhood homes; both of them my Jewish forebears’ homes. The blood of my working-class Moravian-born immigrant great-grandfather was spilt, probably in France, in order to seal that link forever. ‘דאָרטען, װאוּ מיר לעבען, דארט איז אונזער לאנד. Dorten, vau mir lebn, dart iz aunzer land.’ Alfréd Danzer may not have been an ideological Bundist, but he lived and suffered like one. How strange it is, then, that I should be a migratory bird, a weird and hopelessly-fragmented kind of pilgrim, an assimilated-apostate Jew wandering in search of Christ on the wrong end of another continent!

So there I was in Qazaqstan: a nervous wreck and a broken failure on the verge of washing out of Peace Corps. I went to the hram of Saint Aleksandr Nevsky looking for… I don’t even know what it was anymore. Father Valery (Shurkin), the rector of that parish where Saint Aleksandr was the patron, welcomed me as warmly as if I were another Russian. And he asked me if I was Orthodox; I replied in my broken survival Russian that, no, I belonged to a ‘peace church’. He replied to me, gently, in paraphrase – though I didn’t and couldn’t have known it at the time – the wisdom of Saint John of Shanghai and San Francisco:

That the Kingdom of God is only as ‘close’ as we are to each other, and functions as a kind of inverse-square law bringing people closer as they draw near the source of that radiance, made a kind of intuitive sense to me. It also, I realise in hindsight, authorises a spiritual directive to ‘be where you are’: the light reaches everywhere; you do not have to, and should not, pack up and leave to find it. ‘Dorten, vau mir lebn, dart iz aunzer land.’ (The irony is that I had to travel to Qazaqstan and China to figure that out.) Saint John was a Russian-speaking ethnic Serb from Khar’kov; not a Yiddish-speaking Jew from Kiev. And yet even that propinquity is not an accident; as God sees it, nothing can be. If Jewish Bundism was a political reaction to a bloody kind of settler-colonial imperialist impulse on the part of our own people, then here is the spiritual mirror of that belonging. Orthodox Christianity, too, is a church of empire that doesn’t have to be.

To be a church of empire or a church of the crucified: that was the choice that the princely Saint Aleksandr, the patron of that little hram in Saimasai, had to make. He had cultivated the habits of ‘here-hood’ in his early life by attending closely to local administration in Novgorod and Vladimir, and settling disputes between merchants and craftsmen and boyars. He is most famous, though, for his military victories: winning Davidic battles against the Teutonic Goliaths on his Western frontier – the Swedes at Neva; the Germans and Balts at Peipus. Saint Aleksandr’s military prowess is commemorated in the legendary Sergei Eisenstein film bearing his name, but this is not the most important aspect of his life or character.

When it came to a true choice between worldly glory and Christ-like humility, he opted for the latter, the way of nonviolent resistance and self-abasement over the way of triumphalism. He has never been wholly forgiven for it since (and particularly not by Western-looking Slavs nor by cold-war liberals). The louder the schismatics cry out in false umbrage that he is a proto-Stalinist, the more intensely his example of sublime meekness in the spirit of Saints Boris and Gleb puts the lie to their canards and calumnies. Saint Aleksandr made a prudential decision to surrender his independence to the Khan of the Golden Horde. He gave over vain promises of imperial glory and even his state’s independence from the Tatars, in order to save the lives of his people and the spiritual character of his country. He had to put aside any illusions or delusions of grandeur he might have entertained, and make a decision here and now. He decided in that moment that ‘dorten, vau mir lebn, dart iz aunzer land’, and not some other. He didn’t have to travel to France and fight to seal the link to his home in blood. He did it merely by refusing to run, by refusing to fight, by bowing his head and bearing the Cross where he stood. To that heartsick ‘peace-church’ stranger standing in his temple, somehow he drew close: a ray of light pointing toward the Son.

At the time, the importance of my visit to the hram of Saint Aleksandr had not made itself particularly strongly felt. It was only with a certain distance of time that the full effects of that ‘fragment’ came. But the saint was ‘here’.

In the sense I’m using it, all saints are ‘here’, insofar as they are in Christ. As Saint John says, all those who have drawn close enough to God to be so glorified have, by so doing, drawn close to those here on earth as well. Grace knows no worldly borders. Rather, Christ and His saints draw near to those of us who are in need of grace. Christ’s blood is indeed a seal upon us, linking us indelibly to the Heavenly Kingdom in the Eucharist, no matter where we are. ‘Dorten, vau Dir lebn, dart iz aunzer land.’ The Crucifixion and Resurrection are historically- and gæographically-particular events that themselves shatter the logic of history and gæography. It is only we, limited as we are, who are in need of particularity and mediation. In that sense the blood of the saints truly is a seed. It falls to us to cultivate it.

I am tied to my homeland – the Upper Midwest, broadly – in a way which is completely belied by my peregrinating youth and young-adulthood. Bundism is in my Jewish-American heritage even if my amnesiac double-mindedness ‘forgets’ it, strives and rebels against it; though it belongs to a non-Christian tradition it nonetheless informs my Orthodoxy. And there, in that space where the local and the universal dissolve, there are some voices and some faces that figure with greater prominence. The humble Saint Aleksandr of that Qazaqstani temple is one. The others may be familiar to readers of this blog. Some, like Saint John of Riga, drew near to me in my wanderings abroad. Others, like Saint Alexis of Wilkes-Barre, were waiting for me at journey’s end. The examples of these saints, already remembered eternally by God, can help me – an ignorant slave, like Meno’s – to remember what I have forgotten.

I am an amnesiac. I am an American. The two go together, and not altogether on account of the alliteration. And it would go together with being a son of Adam, for that matter – poor bloke got tricked into eating a fruit and forgot what good and evil were. My amnesia gives me a double mind; it is not the cause of my guilt, but I am guilty of it anyway. Věra Danzer Cooper – the Jewish grandmother I never knew, and never knew I had until high school – has been something of a haunting presence in my life: more so than I would have thought possible at the time. The sweet and smiling face in the yellowed photographs, almost the double of my younger sister’s, somehow ‘clicked’ something in my mind. Separated as we were by generations (but not by gæography, she also a Wisconsin girl planted in Rhode Island!), she made certain abstractions concrete. She sparked in me a fascination with genealogy, which in turn led me to discover certain rhymes and patterns in my own family life. Blood is thicker than water. Water evaporates. Blood leaves marks and scars. Both flowed from the side of Christ, pierced by a Roman spear at the behest of my kin. Tertullian talked about the ‘blood of the saints’ as the ‘seed of the Church’. There’s a truth in that, but we’ll get to it later.

Blood links me indelibly to Wisconsin and to Rhode Island – both of them my childhood homes; both of them my Jewish forebears’ homes. The blood of my working-class Moravian-born immigrant great-grandfather was spilt, probably in France, in order to seal that link forever. ‘דאָרטען, װאוּ מיר לעבען, דארט איז אונזער לאנד. Dorten, vau mir lebn, dart iz aunzer land.’ Alfréd Danzer may not have been an ideological Bundist, but he lived and suffered like one. How strange it is, then, that I should be a migratory bird, a weird and hopelessly-fragmented kind of pilgrim, an assimilated-apostate Jew wandering in search of Christ on the wrong end of another continent!

So there I was in Qazaqstan: a nervous wreck and a broken failure on the verge of washing out of Peace Corps. I went to the hram of Saint Aleksandr Nevsky looking for… I don’t even know what it was anymore. Father Valery (Shurkin), the rector of that parish where Saint Aleksandr was the patron, welcomed me as warmly as if I were another Russian. And he asked me if I was Orthodox; I replied in my broken survival Russian that, no, I belonged to a ‘peace church’. He replied to me, gently, in paraphrase – though I didn’t and couldn’t have known it at the time – the wisdom of Saint John of Shanghai and San Francisco:

The closer we approach God, the closer we approach each other, just as the closer rays of light are to each other, the closer they are to the Sun. In the coming Kingdom of God there will be unity, mutual love and concord.