27 January 2015

The Shoah, through American eyes

On Holocaust Remembrance Day, we should remember that there are several ways for an American to remember the Shoah, some of them helpful and others far less so. World War II is a living memory for some, but it is a living memory which is rapidly fading. As a millennial, my grandparents lived through the War – at least one of them witnessed the Pacific theatre firsthand. But of these grandparents, two of them are now dead. And my Jewish grandmother was lucky to have been born to immigrant parents in Wisconsin rather than stay in Europe, where she would have been forced into an Austro-Hungarian ghetto or into a Nazi concentration camp. As such, my experience of the Shoah is the same as that of any American Jew whose family immigrated early: I know of the Shoah only intellectually, through films and through books, and not through a personal narrative. But insofar as it was an attack on specifically ethnic, not religious, Jewishness everywhere, it nevertheless has a personal impact that does echo down to this day.

So what do we do with it?

First off, not only Jews suffered in the Shoah. The suffering of the Jews was particular and unique in terms of the full social and historical depth of the animosity toward them drawn upon by the Nazis and in terms of the symbolic value the death of the Jews held for their persecutors. But in the end it was a shared suffering – shared with Poles and Russians and Serbs, shared with trade unionists and political leftists of all sorts, shared with Romani, shared with the disabled and mentally-ill, shared with homosexuals, shared with all manner of social outcasts and scapegoats. One unproductive way to look at the Shoah is to wrongly essentialise the suffering of one’s own group, and to use it as a totem against others who were hurt and whose communities were destroyed.

On the other hand, there was a unique dimension to the Shoah, unlike any other event in Western history. To look at it as an atrocity like unto all other atrocities committed by world powers throughout history also is reductively relativistic, and therefore wrong, because it excuses all the people who do not deserve to be excused. The spiritual rot of anti-Semitism took hold at the very heart of the Western world, at the very pinnacle of the most intellectually-advanced Western society, and culminated in an industrialised bloodshed of such enormity that, for a brief time, it shocked the Western world into introspection about its own commitments. In this, the Shoah was very much unique, and Jewish suffering in it was unlike unto anything else in the history of the West. That the Germans in their utterly blind, Nimrodic spiritual pride, were so convinced of the superiority of their civilisation that so many of them were seduced by Hitler’s poison, deserves to be marked off. The Nazi hatred of the Jews itself masked a hatred of all godhoods but their own. There is an example there that now needs to be rightly understood by the modern West.

Whether it actually is so understood is another matter.

The Holocaust was born of the first and gravest of sins – hubris, the sin of the Evil One. We must take care that its remembrance does not do the same. It is actually not as clear to me anymore which is worse – the denial of the Holocaust or the manipulative use of the Holocaust to justify further acts of Western civilisational hubris (the wars in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria and the Ukraine), and to indulge in the idea that the world and its people are ours to reshape in our own image. The former, though it goes without saying that it is a morally repugnant wilful blindness and deserves the highest censure, has at least the virtue of being a direct reactiveness, a pride expressed in the bluntest of possible forms: ‘I could not have done that’.

The latter, on the other hand, though its intentions are sincere – ‘never again’ as a battle-cry in the name of human rights and democracy – nonetheless masks the same spiritual illness that had taken hold of the Nazis. The pride takes a subtler turn. For the civilisation that understands itself as the ‘thousand year kingdom’, or in terms of the neoconservative and democratic-idealist discourse the ‘end of history’, dissent is tantamount to an existential threat and must be utterly erased. It is no accident that the cheerleaders of the war in Iraq compared Saddam to Hitler, or that Gadhafi, Assad, Putin and Xi have all come in for the same utterly-undeserved comparison from precisely the same people. It was a psychological need to highlight the cosmic and world-historical consequences of the failure to act to stamp out the dissenters from our designs and calculations. The same hubristic spirit of the will to power, of the self-justifying drive for mastery over man and nature, that drove the Nazis to their spectacular fall into the most animalistic depravities against the Jews, still wriggles like a worm around the very heart of liberal, democratic Western civilisation. Thus, to take the Holocaust as an object lesson in the self-justification of the merits of liberal democracy, rather than as an indictment of our spiritual disease, ultimately strikes me as equally wrong.

For this reason alone, the Holocaust ought to remain close to our minds. We as Westerners stand before it – not as the prosecutors, but as the accused. The fact of Jewishness places an additional burden upon those of us who are Jewish as well as Americans, because even though we have not personally suffered in the enormity of the Shoah, we have been chosen inescapably as witnesses for the prosecution. And we will remain witnesses. But as the beneficiaries of American civilisation and military action, we are very much not exempt from the indictment upon which the Nazis have been judged. We need to remember the Shoah, but we need to remember it rightly. Contra Nietzsche, memory must not yield to pride. We must attain from the Holocaust that spiritual knowledge that comes only through our willing repentance, or the battle-cry of ‘never again’ will ring truly hollow indeed.

25 January 2015

Almost wholly malign

So, when Kim Jong Il died back in 2011, did President Obama reroute his itinerary for a personal visit to Pyeongyang, to pay his respects to the late dictator’s next of kin? Did Obama give a public statement valuing Dear Leader’s perspective, cherishing his genuine and warm friendship, and praising the courage of his convictions? On the day that Fidel Castro gives up the ghost, will Prime Minister Cameron (or whoever holds office at that time) publicly remember his long years of service to the revolution, his commitment to peace and his strengthening the understanding between faiths?

For the first, absolutely not. And for the second, I’m not holding my breath. And both would have good grounds, because each regime as represented by its respective head of state is unworthy of our sympathies.

But far, far less worthy is the Saudi regime.

Remember that this is a country where mutilation is the prescribed punishment for theft and other crimes; where women are not legally allowed to drive, to give their own sworn testimony in a court of law; where slavery is still openly permitted; where people are still beheaded for witchcraft; and where a Burmese woman was recently paraded through the streets and then beheaded publicly whilst being held down by four Saudi policemen, protesting her innocence until the end. This horrifically brutal dictatorship has sentenced a man to 1000 lashes for the crime of blogging. And for the poor people who are unfortunate enough to live under Saudi rule, even those who are not migrant labourers, everyday existence is an almost intolerable oppression from which the only psychological escape is in casual homosexuality, extreme motor stunts and other high-risk behaviours. Not even North Korea under the Kims, for all its forced labour camps and its own culture of summary executions, is as animalistically brutal or callous as Saudi Arabia.

And it should also be considered that private Saudi oil barons have been some of the most lucrative and steady supporters of al-Qaeda, the al-Nusra Front and, more recently, Daesh. And the Saudi royals turned a blind eye when they weren’t actively helping themselves. As Andrew Brown put it, ‘Saudi’s influence on the outside world is almost wholly malign. It has spread a poisonous form of Islam throughout Europe with its subsidies, and corrupted western politicians and businessmen with its culture of bribery. The Saudis have always appealed to the worst forms of western imperialism: their contempt for other Muslims is as great as any American nationalist’s.’

There is only one reason why Obama and Cameron have been so obsequiously assiduous in paying their nausea-inducing, toadying respects to someone who for his entire public life represented one of the legitimately most evil regimes on the planet – to reiterate, worse than Kim Jong-Il or his son – and it does not speak well of us. It’s not even all about the oil anymore, though that will certainly always remain in the background for such a massive producer as Saudi. But really – it’s the guns, stupid. Never mind that these guns work their way into the hands of people who use them to extort, rape and butcher innocent people – not only Christians and Shi’ites, but Sunnis as well – in Syria and Iraq, and would love to use them to kill us. Weapons contractors in the West must be made wealthy at any cost, and the Saudis are willing to do it.

Hell, even all of the news outlets which I have referenced above, who cannot even rightly claim ignorance on the abuses the House of Saud have perpetrated around the world and in their own backyard, have joined in this vile song-and-dance routine, portraying the late tyrant in the most flattering possible terms. The New York Times was of course dutiful and punctual with its obsequies. Predictably, CNN praised him as a ‘cautious reformer’ and FOX News as a ‘powerful US ally’ in the War on Terror. NPR went even further, quoting Ford Fraker in hailing him as a ‘charismatic’ leader who ‘actually moved people to tears’.

Even worse still, they give this ovation to a man who ruthlessly and viciously stomped all over all manner of freedom of expression in his own country with the sentencing of Raif Badawi, just after having pounded their chests about standing up for the same in France.

Lord, have mercy upon us. We desperately need it.

For the first, absolutely not. And for the second, I’m not holding my breath. And both would have good grounds, because each regime as represented by its respective head of state is unworthy of our sympathies.

But far, far less worthy is the Saudi regime.

Remember that this is a country where mutilation is the prescribed punishment for theft and other crimes; where women are not legally allowed to drive, to give their own sworn testimony in a court of law; where slavery is still openly permitted; where people are still beheaded for witchcraft; and where a Burmese woman was recently paraded through the streets and then beheaded publicly whilst being held down by four Saudi policemen, protesting her innocence until the end. This horrifically brutal dictatorship has sentenced a man to 1000 lashes for the crime of blogging. And for the poor people who are unfortunate enough to live under Saudi rule, even those who are not migrant labourers, everyday existence is an almost intolerable oppression from which the only psychological escape is in casual homosexuality, extreme motor stunts and other high-risk behaviours. Not even North Korea under the Kims, for all its forced labour camps and its own culture of summary executions, is as animalistically brutal or callous as Saudi Arabia.

And it should also be considered that private Saudi oil barons have been some of the most lucrative and steady supporters of al-Qaeda, the al-Nusra Front and, more recently, Daesh. And the Saudi royals turned a blind eye when they weren’t actively helping themselves. As Andrew Brown put it, ‘Saudi’s influence on the outside world is almost wholly malign. It has spread a poisonous form of Islam throughout Europe with its subsidies, and corrupted western politicians and businessmen with its culture of bribery. The Saudis have always appealed to the worst forms of western imperialism: their contempt for other Muslims is as great as any American nationalist’s.’

There is only one reason why Obama and Cameron have been so obsequiously assiduous in paying their nausea-inducing, toadying respects to someone who for his entire public life represented one of the legitimately most evil regimes on the planet – to reiterate, worse than Kim Jong-Il or his son – and it does not speak well of us. It’s not even all about the oil anymore, though that will certainly always remain in the background for such a massive producer as Saudi. But really – it’s the guns, stupid. Never mind that these guns work their way into the hands of people who use them to extort, rape and butcher innocent people – not only Christians and Shi’ites, but Sunnis as well – in Syria and Iraq, and would love to use them to kill us. Weapons contractors in the West must be made wealthy at any cost, and the Saudis are willing to do it.

Hell, even all of the news outlets which I have referenced above, who cannot even rightly claim ignorance on the abuses the House of Saud have perpetrated around the world and in their own backyard, have joined in this vile song-and-dance routine, portraying the late tyrant in the most flattering possible terms. The New York Times was of course dutiful and punctual with its obsequies. Predictably, CNN praised him as a ‘cautious reformer’ and FOX News as a ‘powerful US ally’ in the War on Terror. NPR went even further, quoting Ford Fraker in hailing him as a ‘charismatic’ leader who ‘actually moved people to tears’.

Even worse still, they give this ovation to a man who ruthlessly and viciously stomped all over all manner of freedom of expression in his own country with the sentencing of Raif Badawi, just after having pounded their chests about standing up for the same in France.

Lord, have mercy upon us. We desperately need it.

22 January 2015

Thoughts on the state of the Union

The problem with the State of the Union address is that, from the way it is structured and from the way the expectations surrounding it are driven, it is often couched in a lingo that is meant to obscure more than it clarifies. The result is something that sounds more like a mission statement than something which honestly clarifies the ‘state of the Union’. The most recent such speech is no exception to this rule.

It is a standby of American politics to conflate the ‘middle class’ with whomever one takes as one’s political totem – the small suburban businessman or the urban petit bourgeoisie – and then to expand the definition of ‘middle class’ to include whomever one likes. What President Obama just did in this State of the Union address was precisely this. First he built a case for ‘middle-class economics’ from the left by using the anecdote of one working-class family (Rebekah and Ben and their two kids); and then he proceeded to elucidate what he meant by ‘middle-class economics’. In fact, Obama’s vision bears no resemblance to an economics of the working class, or even of the middle class. All the language of the ‘new economy’ notwithstanding, when one looks at the details – expanded infrastructure spending (schools, colleges, the Internet), federal childcare programmes, federal community college funding – it is by and large a watered-down American System Whiggism of Henry Clay ca. 1816 with some elite Victorian do-goodism sprinkled in for good measure, repackaged for a 21st-century audience.

There’s actually nothing intrinsically wrong with some of the things President Obama claims to want. An federal minimum wage increase is long-overdue; as is paid maternity leave. Each taken on its own, they would help to increase the self-sufficiency and relieve the burdens on the time and energy of working-class families. But when combined with the federal programmes for childcare and education, even though they are intended to decrease the burden on working- and middle-class families, they in fact signal a decrease of the family’s power to be self-sufficient, and indeed place more real decision-making power in the hands of corporations. Do we really want a higher-educational curriculum dictated by the economic demands of CVS and UPS, Google and eBay, for example?

And there are other highly-troubling aspects of Obama’s plan. He very nearly shows his full hand when he starts speaking about infrastructure – it’s not working-class families, middle-class families or traditional small businesses that are meant to benefit from the new federal investments. It’s the big multinational financial giants, the multinational corporations and the global tech companies that will benefit. The ones who will directly benefit from the powers that Obama is asking for, to sign the still bafflingly-opaque TTIP and the TPP trade pacts (though he doesn’t mention these by name), will not be the average American working-man. It is very clear that the rules of these trade agreements will not be written by the people Obama is claiming to help.

And, of course, the military jingoism which we have come to expect from an Obama presidency is also here on full display: the uncritical embrace of military unilateralism, the vacuous assurances that powers of extrajudicial-execution-by-drone are ‘properly constrained’ in the right hands, the breathtaking hypocrisy of Obama’s assertion of ‘the principle that bigger nations can’t bully the small’, mere sentences after mentioning Syria. It is telling indeed, that the sole highlighted difference between the Republican and the Democratic approach to international relations one of adjectival semantics: a Democratic president gets to say, essentially, that the only difference between his foreign policy and a Republican one is that the latter is ‘fearful’, ‘reactive’ and ‘costly’.

Of course, for those who like their jingo and neoliberalism served neat, still further devoid of content and packaged in sappy condescending platitudes, or with perhaps a slight twist of Jacksonian rhetoric, the response from Senator Joni Ernst would probably be more appealing. (Myself, I had even more trouble wading through that than I did the transcript of Obama’s speech, feeling all the while that both would have a cumulative radiological impact on my IQ.) But what strikes me as I read each of the responses is how similar they are in their substance.

I’m not usually one to trot out the ‘both parties are the same’ line, because they aren’t – they do represent, supposedly, different political strands in the American fabric. Though traditionally the Democrats were the party of the big frontier and the solid South, having risen out of the campaigning tactics and ideology of the aforementioned Andrew Jackson, nowadays the Democratic base has shifted solidly toward the Northeast and has come to encompass a kind of bland Whiggism, for want of a better word: a carefully ‘non-judgemental’ elite social libertarianism combined with a penchant for grand technocratic projects undertaken on a nation-wide scale. The Republican Party, on the other hand, though it has largely always been and continues to be the party of Big Business, nowadays it has taken to heart the fact that Jacksonian pandering to the lowest common denominator is a winning strategy. And since the 1970’s in any event, the Republicans have managed to attract into their membership the old white Southern Dixiecrats who represented Calhoun’s strain of resource-rentier politics, complete with their quasi-libertarian ‘states’-rights’ gloss.

Personally, my own political commitments are much more akin to the Canadian red Tories than to anything currently on offer in my own country (though I confess to feeling a certain affinity for the Midwestern radicalism born of the Achtundvierziger generation of Central European immigrants). However I still find lamentable the lapse, if not loss, of the venerable old-style federalist New England conservative in the mould of John Adams. The gradual abdication of the Boston Brahmin as a class from its place in American politics, along with its traditional sense of noblesse oblige, is a tragedy. I would dearly love to see the return of a cultured politics which are solidly anti-war and realist in foreign outlook, sceptical of democratic excesses, and favourable to small American businesses and a robust, interventionist and moderately-paternalistic federal government.

The sad fact of our state of the union, is that both established political parties are now offering us a ballooning national security state, military commitments that recognise no proper limits, a trade apparatus which is completely unaccountable either to American businesses or to American workers, and policies which appear designed to entrench and enrich the already obscenely-wealthy. We need either better radicals or better conservatives. Preferably both.

Labels:

Arkona,

Blue Europa,

culture,

history,

lefty stuff,

Mizheekay Minisi,

politics,

Teutonia,

Toryism,

Whiggery

Fei Xiaotong’s ‘distributism with Chinese characteristics’

At the strong encouragement of my remarkably intuitive, loving and peerless wife Jessie, I undertook to read this past week From the Soil: the Foundations of Chinese Society 《鄉土中國》 by Fei Xiaotong, who is rightly credited as the father of Chinese sociology. Though he was born in Suzhou and his entire educational career was spent within China, at Yenching and Tsinghua Universities, he was inspired by the teaching of University of Chicago urban sociologist Robert Park, from having studied with him in 1932. He was later tutored in methods by White Russian ethnographer Sergei Mikhailovich Shirokogorov (whom Dr. Fei credits as his deepest influence), and by functionalist Austro-Polish anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski. His studies of sociology were driven by an earnest and heartfelt desire to reform China; and even though he writes in a concise and meticulously neutral prose, attempting to lay before his readers a careful bird’s-eye view of the differences between the rural Chinese and the modern Western modi vivendi, he can never wholly disguise his sympathies or compassion for the rural Chinese. Even the goal of this anthology of short essays I read is to meet rural Chinese communities where they are.

As such, I would highly recommend it to anyone seeking to visit or understand China, let alone live here. I would argue that it is as important a book for understanding Chinese people as Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America is for understanding Americans – and that is no idle comparison. I have said elsewhere (with my tongue only half-in-cheek) that Dr. Fei ought to have subtitled it instead Everything You Wanted to Know About China, but Were Afraid to Ask. Starting from the standpoint of understanding what is materially important in Chinese rural life, where everyday interactions are marked by intimate familiarity with neighbours; sedentary living; a slow pace; a style of knowledge that is best transmitted orally and through practice from elders to the young; and a need to band together in extended family groups to get anything done on a large scale, he carefully reconstructs Chinese social relations. If you ever wanted to know why Chinese people in practice may have a high tolerance for what we might see as ‘corrupt’ practices; why Chinese married couples so rarely show their emotions for each other; why Chinese ‘drinking buddies’ and ‘girl-friends’ do show so much emotion for each other; why ‘rule of law’ is still something of a dirty word in some quarters; why Chinese people give so many gifts to each other (even when Westerners might see it as bribery); why they fight to foot the bill when they eat out; why they seemingly value the extended family over the nuclear family; why ‘civil society’ in China is so different; why many people don’t seem to care about their own national politics; and why the people who run small shops and street stalls always seem to be from ‘out of town’ in any Chinese town or village – this is certainly the book for you.

This book is most famous, actually, for one analogy Fei Xiaotong makes regarding social relations in West and East. He sees Western society, with its ‘organisational mode of association’, as analogous to a bundle of straws or sticks. Each straw or stick is distinct and separate and – to an extent – equal and interchangeable with any other, and they are stacked together in discrete, exclusive bunches. He recommends seeing Chinese society through the lens of a ‘differential mode of association’, and borrows the explicitly Confucian analogy of ripples in a pond, emanating outwards from where a stone was cast in. Each person is his own ‘centre’ of a network of fluid and overlapping relationships, and his duties within each are either more important or less important depending on how near another person is to him. Western societies tend toward universalisable theories of social ethics; the Chinese toward situated ethics of care.

But although all of the above are carefully and sometimes critically explained, one has to remember that Dr. Fei is writing for a Chinese audience and introducing Western categories for comparison. And he is writing from a standpoint of sincere sympathy for the rural Chinese view. He speaks even the neutral and often one-sided language of his field with a heart full of love. Even though he is clearly an advocate for social reforms, rural literacy and democratic rule, the entire point of his work is that he wants it done in a way which respects the values and lifeways of rural Chinese culture. In his view, reform badly imposed – for the wrong reasons, or from a Western rather than a Chinese frame of reference – would be worse than no reform at all.

Unfortunately, Dr. Fei’s work would not only go unregarded, but he would be punished for it by the government that took control in 1949 – a government which he himself supported! – and abolished the entire scholarly field of sociology a mere three years later. Branded as a bourgeois ‘rightist’ in the Cultural Revolution for his proposals, the Chinese government banned his work, forced him to publicly recant it, stripped the father of Chinese sociology of his scholarly position and sent him to work cleaning privies. Ironically, in Taiwan, Dr. Fei’s work was banned for the exact opposite reason. He had been anti-Nationalist and, in the last instance, a supporter of Mao. But his work managed to circulate samizdat-style on the black market in the Republic of China, where some of his proposals were tentatively implemented by the government – though naturally he never got any credit for them.

I was lucky to pick up the translation I did, because in the postscript the translator also includes an overview and excerpts from Fei Xiaotong’s companion anthology Reconstructing Rural China 《鄉土重建》, which actually provides some of the policy prescriptions he advocated in light of his sociological inquiries.

Dr. Fei was convinced that if modern industry and knowledge were to flourish in China in a healthy way, the large landholding class would have to give up their traditional privileges and, under the aegis of a compensated land reform policy, break up and distribute holdings to individual ‘families’ (defined not as Western nuclear families, but rather individual ‘small lineage’ units under a single patriarch). The landlords would then be compensated with government bonds to be used for small-scale capital investment.

But in spite of this decentralist, market-oriented approach, to the end Dr. Fei was emphatically not the bourgeois ‘rightist’ the Cultural Revolution had made him out to be. Indeed, he wanted to see industry in the hands of local villages and townships, focussing on handicrafts, household workshops and light industries, owned and run cooperatively. To quote the good Dr. Fei himself: ‘What I call rural industry includes the following elements: (1) Peasant families participate in industry without giving up farming. (2) The location of industries is scattered in and around villages. (3) Such industries belong to the peasants who participate in them; therefore, ownership is cooperative. (4) The raw material for such industries is mainly produced by the peasants themselves. (5) Most important, the profits from the industry are directly distributed to the peasants.’

Though being written in 1948, From the Soil and Reconstructing Rural China predate Small Is Beautiful by a good twenty years or more, and though they are writing for very different audiences, the ideas of Fei Xiaotong and E. F. Schumacher on rural development bear a remarkable resemblance. The land reform and household industry policies which met with such success when adopted by the Nationalists in Taiwan, the editors of the volume surmise, actually owe much of their content to Dr. Fei’s prescriptions.

The People’s Republic of China is often held up by its anti-capitalist, democratic and localist critics as an example of how not to do rural development. The point of interest here, though, is that there were people discussing such ideas even during the early People’s Republic period – and that Chinese culture itself does not necessarily doom the adoption of distributist, localist or economic-democratic policies. Indeed, if Dr. Fei is to be believed – and Taiwan’s experience seems to suggest he is – Chinese culture is actually very well-suited to these policies as a culturally-distinctive alternative, both to Washington Consensus laissez-faire and to the state capitalism of the modern Chinese Communist Party.

Labels:

Arkona,

books,

Confucianism,

culture,

history,

Holmgård and Beyond,

Huaxia,

lefty stuff,

Mizheekay Minisi,

œconomics,

politics

13 January 2015

More on feminism, courtship, rites-of-passage and nerd shaming

Full disclosure: I am a nerd. I come from a family of STEM Ph.D.s and am the oddball in the family having gone into philosophy and economics, and have made up for it with interests such as computer gaming, manga, D&D, Star Trek, Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter and other speculative fiction (like the Space Trilogy and the works of Lois McMaster Bujold). I am also from a fairly ‘privileged’ (in the conventional sense) background, having been born to a bourgeois Anglo family with a non-ethnic surname. And I also have a troubled relationship with feminism – having oscillated between full-out opposition and equally full-out support during college and having found myself staking out a claim in a halfway field of clarifications and nuance ever since. The most complete of which, I think, I have written here at Solidarity Hall – mostly in agreement with contrarian-left historian and social critic Christopher Lasch.

So let me put it bluntly. I feel for Scott Aaronson. Full stop.

I won’t patronize him by saying I know just what he went through. But some of the discrete elements he describes: of shame, of paralysing self-awareness, of the natural desires for emotional and physical closeness, of trying to wish these desires away, of relations with women which were thereby characterised by a stiffness and remoteness (neither of which is an attractive trait in either gender!) reinforced by the fear of being an uncontrollable sex-crazed monster, of the ease with which all these things could sour into self-loathing and resentment of the people who were sexually ‘successful’ (men and women both!) – these things I can identify with. These things were real, they were reinforced from the outside, and they were problems. I can remember in high school and college many periods when I was made to feel each one of the above things – though perhaps not to the degree Scott Aaronson did. (I never sought out Andrea Dworkin’s work, for example.)

And I have also read the responses. In fact, I read one of the responses (Laurie Penny’s) before I actually read the good computer scientist’s comment which inspired them, which ought to tell one something. The most execrable of these were mostly anti-intellectual, knee-jerk, rage-fuelled exercises in attempting to reinforce and amplify every single one of Dr. Aaronson’s former neuroses about dealing with women, and being thus, they aren’t worthy of a serious response.

This one, the aforementioned one written by Laurie Penny, is far less knee-jerk and even perhaps well-intentioned, but still falls into the trap of misinterpreting most nerds’ motivations and absolutising social ‘privilege’ along a single dimension. This attempt to absolutise one’s own group’s suffering as more essential is merely annoying when directed at nerds, but it becomes seriously more problematic when it is directed at, say, Third World societies or even at black American communities here in the US. ‘Intersectionality’ is, after all, not trivialising someone else’s problems, and not shifting the frame of the conversation toward your own. Certain sections of feminism are far better at talking about ‘intersectionality’ than practicing it. And however well-intentioned and sympathetic Penny’s approach might be, it still manages to expose the fundamental disconnect which makes intersectionality such a problematic concern within feminist circles.

Another written by Jeopardy! champion Arthur Chu may sound more reasonable on its face but still fails to grasp the true and systemic nature of the problem. Social behaviour and psychology are intrinsically linked, as psychology is necessarily shaped and reinforced by social cues and messages. What ‘happens inside [one’s] head’ often has a very real bearing on what ‘happens to’ people in the real world, and vice-versa. To make the requisite nerdy Harry Potter reference and quote the wise Professor Albus Dumbledore: ‘Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?’ Thus, Chu would have been on safer ground if he’d said that rape and harassment of women were a more immanent and morally-immediate problem than the psychology of the male nerd, but instead he tried to posit the former as more ‘real’ than the latter, without trying to understand that nerd psychology and rape are actually equally-real symptoms (albeit not ones of equal moral weight or importance) of the same socio-psychological problem.

Suffice it to say that I don’t think either Scott Aaronson or any of the commenters on his blog are as ‘blind’ as Arthur Chu thinks they are. When speaking about ‘rape culture’, because the perpetrators are so often men whether nerdy or not, psychological issues of men’s self-image and self-worth are inevitably going to come to the fore. I agree completely with feminist commentators and with Arthur Chu, when they say that women being stalked, raped and killed is ‘something that men are doing and that men can stop other men from doing’. But, certain forms of feminist praxis – even moderate feminist praxis – have historically had the precise opposite effect.

What do I mean by this? First, think for a moment about some of the context Aaronson gave to his blog comment – a key part of the context that came in for some of the harshest criticism by Penny. Aaronson says that he might have been just fine under the rules of the traditional rural Ashkenaz community, the shtetl (think Anatevka), and Penny all but accuses him of harbouring a secret yearning for a time when he might have ‘been the legal owner of [a woman’s] body, property and the children [she] would have been expected to have’. To which Aaronson has since amended his comment to add: ‘there were many times and places where marriages did not occur without both parties’ consent, but there was also a ritualised system of courtship that took much of the terror and mystery out of the process’ (emphasis mine).

Let’s do Scott Aaronson the honour of taking him at his word here, and take a closer look at this ‘ritualised system of courtship’. Ritualised systems of courtship were part of a larger societal construct meant to hold men and women at a distance from each other, and in so doing keep the sexes from coming into conflict with each other. Rural, traditional courtship rituals were, at their basis, an acknowledgement of the physiological and psychological distinctions between men and women, and a bargain between them to minimise or ameliorate the conflict between the sexes. As Chinese sociologist Fei Xiaotong puts it: ‘Rural society seeks stability, so it fears the destruction of social relationships. It is Apollonian. The relationship between men and women must be arranged so that their emotional states are not erratic… One need not seek an underlying commonality between men and women; between them, there should be some distance.’ And, more directly, Christopher Lasch: ‘The tradition of gallantry formerly masked and to some degree mitigated the organised oppression of women… Polite conventions, even when they were no more than a façade, provided women with ideological leverage in their struggle to domesticate the wildness and savagery of men. They surrounded essentially exploitive relationships with a network of reciprocal obligations, which if nothing else made exploitation easier to bear.’

Obviously, both Fei and Lasch, and clearly Aaronson also, see that this setup is not optimal – particularly not from a woman’s point-of-view. But it does have the virtue of taking the ‘terror’ out of the courtship process, and prevent that terror from leaking out into the society generally. What does Aaronson mean by this? Well, here is where feminist praxis runs aground against the law of unintended consequences: a big part of (particularly second-wave) feminism took it as a duty to ‘strip away the veil of courtly convention… revealing the sexual antagonisms formerly concealed by the “feminine mystique”’. Lasch in particular notes the result of forcing men and women to regard each other in ways which are completely devoid of even the fictions of sexual civility: ‘Denied illusions of comity, men and women find it more difficult than before to confront each other as friends and lovers, let alone as equals. As male supremacy becomes ideologically untenable, incapable of justifying itself as protection, men assert their domination more directly, in fantasies and occasionally in acts of raw violence.’

Little wonder indeed, that socially-inept and introverted men who find themselves literally terrified by a landscape of dog-eat-dog sexual competition – finding themselves both the ill-equipped competitors of the ‘Neanderthals’ and the easy targets of certain women’s frustrations with men generally – harbour at least a kind of sentimentality for the days of conventional courtship!

Even more generally, though, historical feminist praxis has very often acted as a force for an atomising individualism and, as feminist writer Nancy Fraser herself devastatingly puts it, as ‘capitalism’s handmaiden’. The family being an environment of stifling oppression, so the second-wave feminists reasoned, women ought to be turned out into the marketplace to fend for themselves. The catchphrase became ‘lean in’. The ‘family wage’ – an income that, by definition, sustains a family and allows for the full socialisation of young women and men in the home – is made prima facie suspect by that fact alone. Solidarity within the state was eroded by dovetailing feminist and neoliberal attacks on welfarism. Social solidarity and the possibility of intersectional cooperation were undermined by a greater emphasis on ‘identity’ politics.

But there are still deeper, sociopsychological effects still at play due to this atomisation. As Daniel Schwindt remarks, such individualist praxis as this deprives young men and young women of the stable and vibrant social context and intergenerational support (family and neighbours both) they need to define themselves as adults. It removes all frames of reference for, all mutually-reinforced responsibilities associated with, and all socially-accepted markers of, adulthood. With one highly notable exception, highly painful in its brute biological imperative: that of sex.

And here we find the one place where nerds – young male nerds in particular – are the most disempowered. Adulthood for young men particularly is culturally defined by sexual conquest alone – and not by any significant physical, moral or intellectual achievement unless it brings direct monetary gain. As we have shown above, the death of courtship has made sexual competition even fiercer and more dangerous – for this reason its allure is perversely increased as a field in which a young man must ‘prove himself’. And antipathy for nerds (even and especially when it comes from self-described feminists) is almost always couched in a language that explicitly links failure in sexual exploits to a perpetual childhood: ‘virgin’, ‘man-child’ and ‘mother’s basement’ figure prominently in such abuse, as do acne and vestigial allusions to lack of personal grooming or social aptitude. I can’t stress enough that this is not in the slightest to deny or excuse in the least some of the childish and malicious behaviour that some nerds are capable of, only to highlight the fact that society offers us vanishingly few resources or reasons to overcome such behaviour.

In fact, I suspect this is one of the reasons so many nerds – boy and girl nerds both! – are so strongly, keenly and painfully drawn to fictional portrayals of rites-of-passage and the heroic monomyth. Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, practically every traditional comic superhero mythos, Harry Potter, the sword-and-sorcery novels of Robert E. Howard and Dungeons and Dragons in particular are representative of such fiction. Imperfectly, they stand in for a society which has forgotten how to distinguish a girl from a woman, or a boy from a man, along any dimension other than sexual experience.

Entire tomes could be written on any of the topics mentioned above. And I emphatically don’t want to make feminism the evil Empire of this little space-opera. My only purpose in writing this piece was to highlight where many of the problems in this particular landscape still exist, in a way that respects Scott Aaronson’s personal experience and that of young male geekdom more generally. Like Scott Aaronson and Arthur Chu, I wholeheartedly agree with the feminist demands that we men behave better; they are well-grounded and tragically well-evidenced. My interest, though, is in finding ways to re-equip boys and men with the social and psychological resources we need to do so, which we seem to have lost somewhere along the way.

So let me put it bluntly. I feel for Scott Aaronson. Full stop.

I won’t patronize him by saying I know just what he went through. But some of the discrete elements he describes: of shame, of paralysing self-awareness, of the natural desires for emotional and physical closeness, of trying to wish these desires away, of relations with women which were thereby characterised by a stiffness and remoteness (neither of which is an attractive trait in either gender!) reinforced by the fear of being an uncontrollable sex-crazed monster, of the ease with which all these things could sour into self-loathing and resentment of the people who were sexually ‘successful’ (men and women both!) – these things I can identify with. These things were real, they were reinforced from the outside, and they were problems. I can remember in high school and college many periods when I was made to feel each one of the above things – though perhaps not to the degree Scott Aaronson did. (I never sought out Andrea Dworkin’s work, for example.)

And I have also read the responses. In fact, I read one of the responses (Laurie Penny’s) before I actually read the good computer scientist’s comment which inspired them, which ought to tell one something. The most execrable of these were mostly anti-intellectual, knee-jerk, rage-fuelled exercises in attempting to reinforce and amplify every single one of Dr. Aaronson’s former neuroses about dealing with women, and being thus, they aren’t worthy of a serious response.

This one, the aforementioned one written by Laurie Penny, is far less knee-jerk and even perhaps well-intentioned, but still falls into the trap of misinterpreting most nerds’ motivations and absolutising social ‘privilege’ along a single dimension. This attempt to absolutise one’s own group’s suffering as more essential is merely annoying when directed at nerds, but it becomes seriously more problematic when it is directed at, say, Third World societies or even at black American communities here in the US. ‘Intersectionality’ is, after all, not trivialising someone else’s problems, and not shifting the frame of the conversation toward your own. Certain sections of feminism are far better at talking about ‘intersectionality’ than practicing it. And however well-intentioned and sympathetic Penny’s approach might be, it still manages to expose the fundamental disconnect which makes intersectionality such a problematic concern within feminist circles.

Another written by Jeopardy! champion Arthur Chu may sound more reasonable on its face but still fails to grasp the true and systemic nature of the problem. Social behaviour and psychology are intrinsically linked, as psychology is necessarily shaped and reinforced by social cues and messages. What ‘happens inside [one’s] head’ often has a very real bearing on what ‘happens to’ people in the real world, and vice-versa. To make the requisite nerdy Harry Potter reference and quote the wise Professor Albus Dumbledore: ‘Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?’ Thus, Chu would have been on safer ground if he’d said that rape and harassment of women were a more immanent and morally-immediate problem than the psychology of the male nerd, but instead he tried to posit the former as more ‘real’ than the latter, without trying to understand that nerd psychology and rape are actually equally-real symptoms (albeit not ones of equal moral weight or importance) of the same socio-psychological problem.

Suffice it to say that I don’t think either Scott Aaronson or any of the commenters on his blog are as ‘blind’ as Arthur Chu thinks they are. When speaking about ‘rape culture’, because the perpetrators are so often men whether nerdy or not, psychological issues of men’s self-image and self-worth are inevitably going to come to the fore. I agree completely with feminist commentators and with Arthur Chu, when they say that women being stalked, raped and killed is ‘something that men are doing and that men can stop other men from doing’. But, certain forms of feminist praxis – even moderate feminist praxis – have historically had the precise opposite effect.

What do I mean by this? First, think for a moment about some of the context Aaronson gave to his blog comment – a key part of the context that came in for some of the harshest criticism by Penny. Aaronson says that he might have been just fine under the rules of the traditional rural Ashkenaz community, the shtetl (think Anatevka), and Penny all but accuses him of harbouring a secret yearning for a time when he might have ‘been the legal owner of [a woman’s] body, property and the children [she] would have been expected to have’. To which Aaronson has since amended his comment to add: ‘there were many times and places where marriages did not occur without both parties’ consent, but there was also a ritualised system of courtship that took much of the terror and mystery out of the process’ (emphasis mine).

Let’s do Scott Aaronson the honour of taking him at his word here, and take a closer look at this ‘ritualised system of courtship’. Ritualised systems of courtship were part of a larger societal construct meant to hold men and women at a distance from each other, and in so doing keep the sexes from coming into conflict with each other. Rural, traditional courtship rituals were, at their basis, an acknowledgement of the physiological and psychological distinctions between men and women, and a bargain between them to minimise or ameliorate the conflict between the sexes. As Chinese sociologist Fei Xiaotong puts it: ‘Rural society seeks stability, so it fears the destruction of social relationships. It is Apollonian. The relationship between men and women must be arranged so that their emotional states are not erratic… One need not seek an underlying commonality between men and women; between them, there should be some distance.’ And, more directly, Christopher Lasch: ‘The tradition of gallantry formerly masked and to some degree mitigated the organised oppression of women… Polite conventions, even when they were no more than a façade, provided women with ideological leverage in their struggle to domesticate the wildness and savagery of men. They surrounded essentially exploitive relationships with a network of reciprocal obligations, which if nothing else made exploitation easier to bear.’

Obviously, both Fei and Lasch, and clearly Aaronson also, see that this setup is not optimal – particularly not from a woman’s point-of-view. But it does have the virtue of taking the ‘terror’ out of the courtship process, and prevent that terror from leaking out into the society generally. What does Aaronson mean by this? Well, here is where feminist praxis runs aground against the law of unintended consequences: a big part of (particularly second-wave) feminism took it as a duty to ‘strip away the veil of courtly convention… revealing the sexual antagonisms formerly concealed by the “feminine mystique”’. Lasch in particular notes the result of forcing men and women to regard each other in ways which are completely devoid of even the fictions of sexual civility: ‘Denied illusions of comity, men and women find it more difficult than before to confront each other as friends and lovers, let alone as equals. As male supremacy becomes ideologically untenable, incapable of justifying itself as protection, men assert their domination more directly, in fantasies and occasionally in acts of raw violence.’

Little wonder indeed, that socially-inept and introverted men who find themselves literally terrified by a landscape of dog-eat-dog sexual competition – finding themselves both the ill-equipped competitors of the ‘Neanderthals’ and the easy targets of certain women’s frustrations with men generally – harbour at least a kind of sentimentality for the days of conventional courtship!

Even more generally, though, historical feminist praxis has very often acted as a force for an atomising individualism and, as feminist writer Nancy Fraser herself devastatingly puts it, as ‘capitalism’s handmaiden’. The family being an environment of stifling oppression, so the second-wave feminists reasoned, women ought to be turned out into the marketplace to fend for themselves. The catchphrase became ‘lean in’. The ‘family wage’ – an income that, by definition, sustains a family and allows for the full socialisation of young women and men in the home – is made prima facie suspect by that fact alone. Solidarity within the state was eroded by dovetailing feminist and neoliberal attacks on welfarism. Social solidarity and the possibility of intersectional cooperation were undermined by a greater emphasis on ‘identity’ politics.

But there are still deeper, sociopsychological effects still at play due to this atomisation. As Daniel Schwindt remarks, such individualist praxis as this deprives young men and young women of the stable and vibrant social context and intergenerational support (family and neighbours both) they need to define themselves as adults. It removes all frames of reference for, all mutually-reinforced responsibilities associated with, and all socially-accepted markers of, adulthood. With one highly notable exception, highly painful in its brute biological imperative: that of sex.

And here we find the one place where nerds – young male nerds in particular – are the most disempowered. Adulthood for young men particularly is culturally defined by sexual conquest alone – and not by any significant physical, moral or intellectual achievement unless it brings direct monetary gain. As we have shown above, the death of courtship has made sexual competition even fiercer and more dangerous – for this reason its allure is perversely increased as a field in which a young man must ‘prove himself’. And antipathy for nerds (even and especially when it comes from self-described feminists) is almost always couched in a language that explicitly links failure in sexual exploits to a perpetual childhood: ‘virgin’, ‘man-child’ and ‘mother’s basement’ figure prominently in such abuse, as do acne and vestigial allusions to lack of personal grooming or social aptitude. I can’t stress enough that this is not in the slightest to deny or excuse in the least some of the childish and malicious behaviour that some nerds are capable of, only to highlight the fact that society offers us vanishingly few resources or reasons to overcome such behaviour.

In fact, I suspect this is one of the reasons so many nerds – boy and girl nerds both! – are so strongly, keenly and painfully drawn to fictional portrayals of rites-of-passage and the heroic monomyth. Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, practically every traditional comic superhero mythos, Harry Potter, the sword-and-sorcery novels of Robert E. Howard and Dungeons and Dragons in particular are representative of such fiction. Imperfectly, they stand in for a society which has forgotten how to distinguish a girl from a woman, or a boy from a man, along any dimension other than sexual experience.

Entire tomes could be written on any of the topics mentioned above. And I emphatically don’t want to make feminism the evil Empire of this little space-opera. My only purpose in writing this piece was to highlight where many of the problems in this particular landscape still exist, in a way that respects Scott Aaronson’s personal experience and that of young male geekdom more generally. Like Scott Aaronson and Arthur Chu, I wholeheartedly agree with the feminist demands that we men behave better; they are well-grounded and tragically well-evidenced. My interest, though, is in finding ways to re-equip boys and men with the social and psychological resources we need to do so, which we seem to have lost somewhere along the way.

11 January 2015

The danger of ideological monarchism – Russia

This article, written by The Mad Monarchist, is one of the reasons why I am finding it increasingly difficult to sympathise with a certain kind of doctrinaire, ideological monarchist. I say this as a monarchist who believes, first and foremost, that Our Lord, God and Saviour Jesus Christ is the true and rightful ruler of the cosmos. But I regard with the highest suspicion the sort of monarchism which is willing to ignore, downplay, scoff at, twist around, or override any sort of consideration about the inner life of the society and the subject within that society, for the sake of preserving merely the external forms, however much they have been transfigured into brittle, dry dead husks and meaningless echoes of hierarchies of value long-forgotten.

I am saying this as a monarchist, and as a Slavophil for whom the organic unity of the inner life with its outward expression is the key point. Many will confess Christ with their tongues, but if they do not do so with their hearts and with their deeds, Our Lord will profess unto them upon the Day of Judgement: ‘I never knew you: depart from me, ye that work iniquity.’ When the Japanese slaughtered the innocent and defenceless Empress Myeongseong upon their government’s orders, they will not be excused for that iniquity merely because that government had an Emperor. When wealthy financiers and oil barons from Saudi and Qatar send money and arms to the devils of Daesh who are even now slaughtering the region’s hapless and blameless Christians and Shi’ites, crucifying and mutilating men, raping their daughters and conscripting their sons into their evil ways, those financiers will not be excused merely because they profess loyalty to an Emir or a King. Such ‘monarchies’ are hollow mockeries of the leading values their forms are inherently meant to represent – first and foremost, a care and respect for personality integrated over generations, as opposed to the mere utilitarian and egotist concerns of the present. Such ‘monarchies’ are but one step removed from a government like North Korea, which keeps a form in which the head of state is a purely hereditary office, but whose leading values are devoid of any organic or traditional content.

Here is where the insights of Vladimir Solovyov come in handy. Solovyov was, within the Silver Age of Russian thinking, one of the inheritors of the Czarist Slavophil tradition – and one who actively sought a rapprochement between the Orthodox and Roman Catholic communions, in which rapprochement he firmly believed (Russian patriot that he was) that religious, monarchical Russia would play a key role. Yet he is notable in that he considered very seriously the nature of evil, and his short set of Platonic dialogues War, Progress and the End of History: Three Conversations, Including a Short Story of the Anti-Christ is a very clear example of this consideration. Moral evil, he believed, at its deepest and most insidious will appear upon its face to be a manifestation of the good – but on further inspection one will find that it surreptitiously and sneakily mutilates the good in subtle ways. (In this, Solovyov’s Anti-Christ bears a striking resemblance to the leaders of C.S. Lewis’s N.I.C.E. in That Hideous Strength, but that’s a topic for another essay.)

Notably, Solovyov’s Anti-Christ at first looks and bears all the external marks of goodness. He is young, fit, physically imposing and beautiful, ascetic, to all appearances blameless, a brave military leader, a tireless industrialist, a generous philanthropist – yet it is his inner life which is marked by a pride which refuses to admit any room for Christ. Notably, in Solovyov’s Short Story, the Anti-Christ assumes the title of Roman Emperor, and tempts the Christians of the world away from their faiths in Christ by appealing to their outward appetites for social reform, for individual freedom of inquiry and expression, for external authority, for traditional symbols and asceticism. All the external trappings of the Christian teachings are there in the monarchy of the Anti-Christ, and of course all the trappings of the monarchy are there – but the one thing that is missing is any acknowledgement of Christ himself.

So in answer to the Mad Monarchist’s assertion that Putin is blameworthy for having recognised the historical right but not having simultaneously abdicated and restored the Russian state to the House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov, it is worth considering that such a sudden, precipitous and geometric outward political change, not being reflected in the inner life of the Russian society (mutilated as it has been by the misrule and theft and physical and spiritual impoverishment of both the Soviets and Eltsin’s neoliberals) might be an open invitation to the rule of Anti-Christ. (And a sorry excuse for a traditionalist is he who proposes a counter-revolution on just such terms!)

Two problems present themselves at once. The first is that the Russian nation, in its full generational and spiritual depth, is wounded. Wounds require time to heal, both in human bodies and in societies, and a treatment which does not progress in its proper order and time will likely do as much harm as good. For example, if you are impaled by a deadly foreign instrument – a sword or a beam or a sharp stick – basic first aid practice is not to pull it out at once. The bleeding must be stanched and the impaled area cleaned first before you pull out the impaling object. Russian Orthodox priestly praxis likewise recognises, in treating the spiritually-wounded human sinner, that penitence is a process and not a one-time event. The second is that the doctor administering the treatment must be competent. Now, in a monarchy, the usual case is that the monarch is competent because she has grown up with roots in the state which she is meant to govern. Her father, being king before her, will teach her from the wellsprings of tradition and religious devotion everything she needs to understand about her subjects and her land. But the House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov’s competence is in question precisely on these two points. Note carefully that I have absolutely no doubts about the goodwill, faith and talent in government of Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna Romanova, just as I might have no doubts about the goodwill, faith and intelligence of a self-taught, unlicensed practitioner of medicine. That doesn’t mean she is capable of administering the appropriate treatment of my injury.

The Mad Monarchist claims that Putin is a republican and a secret communist sympathiser, but neither one is very well-evidenced. The primary intellectual influences whom Putin quotes most often, Pyotr Stolypin and Ivan Il’in, were both conservatives and staunch monarchists. In fact, I think the one who sympathises more with the communists and republicans – or rather, who understates the spiritual and material results of their rule – is actually the Mad Monarchist himself. By asserting, as he does, that the only right thing Putin can now do for Russia is to step down and restore the monarchy in its outward form, he is actually downplaying and obfuscating the inner, spiritual wrongs that both communist and liberal-republican ideologies have done there.

Labels:

books,

history,

Holmgård and Beyond,

Joseon,

Levant,

philosophy,

politics,

Toryism,

Yamato

10 January 2015

08 January 2015

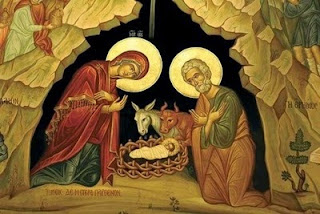

The cataclysm of the Incarnation

On this day (the sixth of January), the Orthodox Christians in Russia, in the Ukraine, in the Caucasus, in the Levant and in East Africa celebrate the Eve of the Nativity, and Roman Catholic and Orthodox Christians in the rest of the world celebrate the Feast of Theophany. Both feasts celebrate the appearance of God Incarnate in the world, and we mark them first with solemn fasting and afterwards with joyous feasting. The disruption of our personal lives in this way, the regular overturning of our normal lives, is symbolic of the cataclysmic nature of the Incarnation. God’s entrance into the world overturns the entire created order.

To give an example of how this is the case, let us consider the Confucian orientation to the created order, which we may take (along with the Greek philosophers) as representative of the heights of innocent pagan piety. In Confucian cosmology, heaven (tian 天) is physically, metaphysically and morally the highest of the moral orders, having given birth to myriad things. After heaven comes earth (di 地), upon both of which human beings and the entire human order (ren 人) depend for sustenance and ritual guidance. In the Old Testament creation narrative, the heavens were created and ordered before the seas and the earth, and human beings last of all. A very similar ordering may be found in Aristotelian cosmology. But this entire construct, which the wisdom of the pagan philosophers all over the civilised world approached, was utterly and completely thrown over, even reversed, in the cataclysm of the Incarnation.

‘He bowed the Heavens and came down,’ so goes David’s song of deliverance in the Psalms, which is repeated in the troparion for the matins of the Nativity Feast. Archimandrite Irenaeus (Steenberg) writes of the event: ‘[i]n the glory of the Incarnation, the divine and the worldly are suddenly, triumphantly, united and transformed… Divine things and human are, in this moment, indistinguishable. Do I behold woman, or throne? Cave, or heaven? Man, or God? The earthly has been brought to the divine and the divine has come to the earthly, and in this most awesome mystery we behold a thing “strange and most glorious”. I come and I gaze, but I am struck with awe, for I behold the things of Paradise resting in a cavern’. Heaven no longer stands above and out of reach of the human world, but humbles itself before a human infant, and at that one surrounded not by wealth or riches or even the basics of a secure hearth and home, but by ‘the muddy squalor of the stable’.

Which goes to remind us that even as the cosmic order is thus cataclysmically overturned, so too is the human order. The Most Holy Theotokos herself sang of this overturning as she saluted her cousin Elizabeth: ‘He hath shewed strength with his arm; he hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts. He hath put down the mighty from their seats, and exalted them of low degree. He hath filled the hungry with good things; and the rich he hath sent empty away.’ The magi of the formidable Parthian Empire to the east came to pay tribute and worship not to wealthy and powerful Herod, but to the true King – some homeless infant born in a stable to the wife of a mere carpenter. And Herod himself and all Jerusalem with him were ‘troubled’ even by this report, and reacted the way worldly power tends to react when thus threatened: with extremes of political violence against the weak. Irony and tragedy permeate the story that begins with an angel wishing ‘peace on earth and good will toward all’ – an irony and a tragedy which prefigure the Crucifixion.

The God whose nature surpasses all possible understanding was human. He had a mother. He had neighbours and kin. He had a hometown and a motherland, though these spurned Him, mocked Him, threw Him out and delivered Him up to be killed. He had a trade, and therefore a vocation and – heresy though it is for an American to mention! – a class. He was in every respect fully present in our bounded, grounded, mortal human nature. The universal being beyond being became in some measure sensible to us in our finitude, but He could not have done so without first, not so much subverting, as catastrophically breaking all our expectations.

Nothing I have said so far will likely perturb anyone of the crunchy persuasion, who grasps firstly the need for such a cosmic order, and secondly the world-shattering importance of its having been overturned. But the Incarnation ought to perturb us, as the reality and the personality of Jesus shoot directly at the heart of the questions of locality, universality and belonging on which we place such importance and take it upon ourselves to offer answers, however tentative. Because heaven has bowed before a man, no longer can we seek refuge and security in the order of the cosmos, and we have been given a terrible and unavoidable duty to smash as idols all human pretensions to an ordered cosmos of our own design.

That fascism and communism have presented themselves to us as such false idols, each presenting to us a neatly-orderable cosmos based respectively upon human hierarchies of race and upon the ironclad logic of dialectical materialism, has become blatantly obvious. It is also the well-founded and well-articulated suspicion of many of us who contribute to Solidarity Hall that liberalism and capitalism are also just such false idols. Whilst cloaking themselves behind a Rawlsian masque of neutrality, even as they overtly and covertly undermine the ‘comprehensive doctrines’ by which a great proportion of the world’s population still understand themselves, live their lives and build their communities, liberalism and capitalism both sneak their own ‘comprehensive doctrines’ through the back door.

But this critique – which I share! – does not leave all ‘comprehensive doctrines’ themselves in a position of safety. There are dangers even within the crunchy, traditional worldview of attempting to order the cosmos according to our own design, and of seeking safety away from the cataclysm of the Incarnation. Though the Holy Family remains the basic context of the Incarnation (and is therefore due our honour), hearth-and-home are not to be found amongst them. ‘Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of Man hath not where to lay his head.’ The entirety of the life of the Lord takes place ‘on the way’ – Christ does not speak much about family except to say that those who do the will of God are His family. In the Gospel ‘place’ is something transitory, and those of us who find ourselves out-of-place in a society which no longer respects it ought to embrace the irony and the agony of our position, so to speak. Against our will, we discontents of liberalism have been made pilgrims searching for what we once had. In one 2013 piece at Front Porch Republic, Mark Signorelli drew the very apt (and to me, unwilling global nomad and economic exile that I am, discomfiting) comparison to Aeneas, of those who look for home where ‘home’ has vanished. And even we are privileged beyond measure, when compared with those who face modernity’s more brutal sting – to give but one example, the Palestinians and the Christians of Christ’s own homeland, who flee those who level their homes and churches with bombs and bulldozers, and those who would convert them or put them to the sword.

Those of us who call ourselves traditionalists and crunchy conservatives – and I say this with every respect to the traditionalist-conservative viewpoint which has shaped mine to such a great extent – still run the risk of setting up idols of blood and flesh, of home and hearth and ‘place’. We do so with the best of intentions. We rightly militate against disembodied desire, against the destruction of the mediating authorities of family and society, against the modernist betrayal of Incarnation. We rightly eschew the madness of ideological make-the-world-anew schemes. But the return to a Victorian-bourgeois, a feudal-mediaeval or a Roman model of domesticity would not be desirable, either, even if it were possible. The cataclysm of Incarnation demands an ethic of place, yes – but it demands also the much more radical ethic of pilgrimage.

Labels:

culture,

politics,

Pravoslávie,

theology,

Viri Romæ

06 January 2015

Christ is born; glorify Him!

Christ is born; glorify Him! Christ comes from Heaven; go and meet Him! Christ is on earth; be ye lifted up! Sing to the Lord, all the earth!

It is best to let our beloved Patriarch have the word on this occasion, as he has a great gift for them. Many blessings for the Christmas season indeed, gentle readers! May all the joy which visited those who saw and knew of our newborn Saviour be with you!

Pointless video post – ‘Плач о радости’ by Black Coffee

Black Coffee (Черный Кофе) is one of those bands that I need to kick myself for not having gotten into earlier. Contemporary to acts like Мастер and Ария, Black Coffee was the main project of Dmitry Varshavsky, whose Orthodox Christian convictions and Slavophil-tinged Russian patriotism manage to spill over into his music (as on this song, from their album Alexandria). Black Coffee started with a very NWoBHM-influenced hard rock sound on their debut, Переступи порог, but quite quickly made the shift into hair metal by the time Golden Lady came out. However, Alexandria marked a return to their heavier roots. Gone is the glammy wailing and shimmery synth work of the first few albums from Alexandria, replaced as it is by a more sombre, more emotionally-charged vocal performance from Varshavsky. The guitar-work is also much more stripped-down, crunchy and heavy, reflecting an almost power-metallic shift. This song in particular uses a masterful thrashy riff, and a very effective guitar solo. Please enjoy, gentle listeners!

And a very happy Eve of the Nativity to all!

Labels:

Britannia,

Holmgård and Beyond,

metal,

music,

Pravoslávie

03 January 2015

Iran and the spirit of Christmas

It should not be lost on people that on the approach of the Nativity of Our Lord (or the actual Christmas feast for my gentle readers on the Gregorian calendar), when the magi of Iran came to Jerusalem bearing gifts of frankincense, gold and myrrh to Our Lord the newborn Messiah, the Iranian Red Crescent has agreed, following an appeal by Iranian parliamentarian Yonatan Betkolia, to send a significant aid convoy to the beleaguered Christians of Iraq, including those who are refugees in Kurdistan. Mr. Betkolia has noted also that the Iranian government regularly sends aid to the Christians of Iraq, with special care and attention to refugees.

For one thing, Iran still holds with pride that it is the land of Cyrus the Great, the Anointed One spoken of by the prophet Isaiah, who himself was the guarantor of the rights of religious minorities, the defender of the persecuted and the champion of the displaced and the dispossessed. The spirit of the zeal for truth in Iran, kindled under the Zoroastrian emperors of old and kept burning with the ‘red’ Shi’ites spoken of by Dr. Ali Shariati, still aspires to this goal. Iran, even under their current highly-flawed theocratic government, has never truly forgotten the legacy of the Magi, who came to visit Our Lord when he was born to a poor displaced refugee mother from Egypt, who couldn’t even manage to stay at an inn, and who gave him rich gifts and adulation. Iran’s government is in permanent contact with the Vatican in order to coordinate its aid programmes. Though the people follow Shi’a Islam, who is to condemn the faith of those who feed the hungry, warm the cold and give shelter to the homeless? Especially we, who live under a government which has done so much to add to the sufferings and the sorrows of the Iraqi people.

It is hard for me to shake the suspicion that when the Day of Judgement comes, the people of Iran will stand in far better stead with the Lord for the fruits of their faith than we will. For then as now, also as the Lord spoke in the Gospel of S. Matthew: the Iranian people saw the Lord hungry and gave him food; they saw the Lord homeless and they gave him shelter; they saw the Lord naked and they gave him clothing. May God bless Iran for their selflessness!

For one thing, Iran still holds with pride that it is the land of Cyrus the Great, the Anointed One spoken of by the prophet Isaiah, who himself was the guarantor of the rights of religious minorities, the defender of the persecuted and the champion of the displaced and the dispossessed. The spirit of the zeal for truth in Iran, kindled under the Zoroastrian emperors of old and kept burning with the ‘red’ Shi’ites spoken of by Dr. Ali Shariati, still aspires to this goal. Iran, even under their current highly-flawed theocratic government, has never truly forgotten the legacy of the Magi, who came to visit Our Lord when he was born to a poor displaced refugee mother from Egypt, who couldn’t even manage to stay at an inn, and who gave him rich gifts and adulation. Iran’s government is in permanent contact with the Vatican in order to coordinate its aid programmes. Though the people follow Shi’a Islam, who is to condemn the faith of those who feed the hungry, warm the cold and give shelter to the homeless? Especially we, who live under a government which has done so much to add to the sufferings and the sorrows of the Iraqi people.

It is hard for me to shake the suspicion that when the Day of Judgement comes, the people of Iran will stand in far better stead with the Lord for the fruits of their faith than we will. For then as now, also as the Lord spoke in the Gospel of S. Matthew: the Iranian people saw the Lord hungry and gave him food; they saw the Lord homeless and they gave him shelter; they saw the Lord naked and they gave him clothing. May God bless Iran for their selflessness!

Labels:

Bêt Nahrain,

Eranshahr,

history,

international affairs,

Levant,

prayers,

theology

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)