28 September 2018

Byzantinism and the interwar Czechoslovaks

Ever since that World Bank / World Values Survey study came out demonstrating how Orthodox Christians tend to be worse capitalists than Western Europeans and also to view capitalism with a greater degree of scepticism, I’ve secretly been intrigued by these connexions between the deep habits and Lebenwelt of those who have grown up in religiously-Orthodox countries, and their political behaviour. I wasn’t particularly convinced by the conclusions of the Djankov-Nikolova paper, which struck me as falling into a lazy ipse dixit cultural-essentialist trap and dismissing too cavalierly the proximate negative experiences of post-communism. But I was intrigued nevertheless. (As an Orthodox Christian leftist, how could I not be?) I already touched on this a little bit, I think, in my ‘Red Ruthenia’ piece, which showed some suggestive and intriguing parallels between Eastern Orthodox Church membership in Slovakia and populist / democratic-socialist (as opposed to ethnic-nationalist) politics. I daren’t comment too boldly on my own performance there, but I really hope I didn’t interpret this in the kind of baldly cultural-essentialist way that Djankov and Nikolova did.

Considering the history of Czechoslovakia more broadly, I also think there are intriguing parallels between the rise of Byzantine studies among Bohemian Czechs at the tail end of Habsburg rule, and the rise of Czechoslovakism as a political solution to the dissolution of the Habsburg monarchy. These parallels are particularly intriguing when one considers the distinctly ‘Byzantine’ shape (particularly the back-room intrigues and the intricate but robust balances of political factions) that even Czechoslovak democratic politics took in the period of the First Republic. In addition, Czech philosopher Jozef Matula has a fascinating overview of Byzantine studies and how they closely overlapped with the same Slavist circles from whence emerged the ideologists of Czechoslovakism.

‘With the exception of a rather short episode when Cyril and Methodius led a mission to Great Moravia,’ Jozef Matula begins, ‘the Czech countries have never been under the direct influence of Byzantine civilisation, but have developed in the sphere of Western Latin culture.’ (Ironic, actually, that I should be discussing this on the feast day of Martyr-Duke Václav.) But he goes on to point out that the ‘late’ but relatively-profound interest in Byzantine history, literature and politics among the Czech intelligentsia overlapped to an overwhelming degree with the pan-Slavist political ideals that many Czech public figures espoused. ‘Byzantine studies, from the very beginning, were a historical science closely connected with the pressing political problems of the time.’ It is not an accident that Jaroslav Bidlo, whom Matula describes as the ‘founder of Czechoslovakian Byzantology’, was also a Slavic studies specialist who worked in Poland and the Slavic Balkans.

Bidlo himself was something of a political quietist, but his students ranged from quietly to stridently radical. Matula mentions Karel Škorpil by name, a Slavophil archæologist who sympathised with Bulgarian national liberation, and ‘political idealist’ historian Konstantin Jiriček, both of whom contributed materially to the Bulgarian national renaissance. Another of Bidlo’s students not mentioned by Matula, is the rather oddball Romantic Bulgarian folklorist and populist Nayden Sheytanov, who sought to merge all the South Slavic nations into a ‘Balkano-Bulgarian Titanism’.

Miloš Weingart is another prominent intellectual Byzantinologist, Bulgaria scholar, Czechoslovakist and pan-Slavist whose work makes an appearance in the interwar period, and who is mentioned with approval by Matula. A professor of linguistics and Church Slavonic at the Charles University in Prague, he published numerous works, several of which pertained specifically to the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius in Great Moravia, and to a historical analysis of the development of mediæval Czech and its relationship to Old Church Slavonic. His face was set sternly against ethno-nationalism. As a linguist he militated particularly, through the Prague Linguistics Circle (which included the prominent left-liberal Russian Eurasianist Prince Nikolai Trubetskoi!), against the Czech chauvinist idea of a ‘pure’ Czech language which could be historically isolated from Slovak, and also against the idea that the West Slavic languages were exclusively formed apart from the rest of the Slavic tongues under the influence of the missions of Saints Cyril and Methodius. His historical overview of Byzantine studies shows that it is intertwined even with the first stirrings of Czech and Slovak national sentiment under František Palacký. Needless to say, Dr Weingart is a figure about whom I would like to learn much more.

Another intriguing figure, and one whom I want to study in more depth, is one whom Matula mentions in passing: Milada Paulová, whose work is cited by Daniel Miller in Forging Political Compromise. Paulová, a distinguished Byzantine scholar, Czechoslovakist and Yugoslavia scholar, who became the first female professor in Czechoslovakia in 1925, also at the Charles University in Prague.

What Matula touches on but what I wish he had devoted a bit more space to, is the influence of these Byzantinist-cum-pan-Slavist ideas in the intellectual sphere on politicians like Masaryk, Švehla and Beneš – contemporaries who more or less collaborated smoothly together most of the time (even though most of the time, Švehla and Beneš didn’t trust or even particularly like one another). Both Masaryk and Beneš held mild pro-Russian sympathies, although they tended in different directions. Masaryk himself had Slavophil leanings and welcomed Russian émigrés with open arms, particularly intellectuals, including the Russian Orthodox religious-philosophical father and son Nikolai and Vladimir Lossky. This was a tendency Švehla shared, but to a lesser extent. Beneš, on the other hand, even though he and his mentor Masaryk were both socialists, had more open sympathies with the Soviets – this became apparent particularly in the aftermath of the Second World War.

Actual Orthodox Christians, apart from the Rusins, in the Czech and Slovak lands were rare. There were one or two notable exceptions, like the poet (and possible forger of historical documents) Václav Hanka, and the conservative-nationalist ‘Young Czech’ politician Karel Kramář. But a certain fascination with, respect for, and attempt to emulate certain aspects of Byzantium were apparently much more widespread and influential in the Czech and Slovak lands and had apparently little to do with formal religious affiliation. This seems to be an interesting historical book-end to the process by which Orthodox Christianity in fact spread into the Slavic lands at the hands of Byzantine South Slavic missionaries through the polity of Great Moravia over 1100 years before.

Labels:

culture,

Elláda,

history,

Holmgård and Beyond,

Illyria,

language,

lefty stuff,

œconomics,

politics,

Pravoslávie,

Velká Morava

27 September 2018

Closely reading Metropolitan Tikhon’s pastoral letter

Vladyka Tikhon of our canonical but controversially-autocephalous church has penned a pastoral letter broaching the topic of the autocephaly crisis in the Ukraine, which although far-off and entangled in various other political questions, cannot but closely affect ours. Our good Metropolitan is a shrewd bloke (pardon the informality). This letter has revealed him as far more temperate and far more prudent in the classical senses than I am or would ever have been in his shoes. His language in the letter, particularly in the opening paragraphs, is also considerably more demulcent and lenitive than any I would have used. However, he touches with the needed firmness on the key indispensable points: the first is the explicit prayerful support for his canonical (and officially- and privately-threatened) brother-Metropolitan Onufriy of Kiev; the second is the need for a regular, truly conciliar (read: sobornyi, rather than monological) approach to these questions of autocephaly, which would in fact be truer to the worthier and better historical spirits of the Orthodox tradition.

We call on our clergy, monastics, and faithful to offer their support and fervent prayers for His Beatitude, Metropolitan Onufry, and all the bishops, clergy, monastics, and faithful of the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church. May the Lord grant them continued strength and wisdom in their endeavor to “keep the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (Ephesians 4:3).I welcome and applaud this gentle, but firm and principled, stand by our Metropolitan. There is only one canonical and legitimate Orthodox Church in the Ukraine, and His Beatitude Metropolitan Onufriy and no other is its head; Metropolitan Onufriy is singled out as the keeper of that brotherly and peaceful unity in the Ukrainian Church which is of the Holy Ghost. We in the OCA are called in unequivocal terms to support and pray for him as such. May God indeed bless, preserve and strengthen Metropolitan Onufriy continuing in that rôle. O Lord, save thy people and bless thine inheritance. Grant victories to the Orthodox Christians over their adversaries, and by the virtue of thy Cross preserve thy habitation. However, the more important part of this letter, and indeed the more Orthodox part, comes before this exhortation. The following in particular is worth reflecting on and considering in its profundity.

Our Holy Synod has been apprised of initiatives by His All-Holiness, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, to address this painful situation and has noted the various preliminary responses offered by other Orthodox Churches. In particular, we have received with sorrow, yet with understanding, the decision of the Moscow Patriarchate to cease liturgical commemoration of the Ecumenical Patriarch and suspend concelebration and participation by bishops of the Moscow Patriarchate in inter-Orthodox contexts.This is worth reflecting on at length. The distinct genius of the Orthodox Church – that which has historically kept us from either congealing into a high feudal fiefdom modelled after and competing with the worldly kingdoms, or else flying apart at the seams and disintegrating into tens of thousands of confused bodies haggling over even the most basic tenets of dogma – is our conciliar, that is to say, sobornyi practice. We neither each assert his own particular truth, nor do we rely on any one man to dictate the truth to the rest of us. But instead we come together in the spirit of Truth that has been left to us by Christ and the Holy Spirit… ideally. This is the theoria The praxis, sad to say, has historically been more honoured in the breach than in the observance, whether under the ægis of the Byzantine imperial state or the Russian – but it has been there in fragments, and has always been there, left to be sifted and held up to the light of our limited wisdom by Russian religious philosophers like Khomyakov and Berdyaev.

We are deeply aware of the pain and trauma in the life of Orthodox people caused by ecclesial schism which weakens Orthodox witness and evangelism in society. Such pain and trauma have been wounds in the life of Orthodox Christians in Ukraine for several decades. Schism, division, and mutual antagonism are not only canonical problems—they are pastoral and spiritual challenges demanding the healing power of Christ and Christian faith. We are mindful of the Russian Orthodox Synod’s call to the local autocephalous Churches to “understand the common responsibility for the fate of world Orthodoxy and to initiate a fraternal all-Orthodox discussion of the church situation in Ukraine.”

The Holy Synod of Bishops of the Orthodox Church in America supports the need for regular dialogue at every level and appeals to all local Orthodox Churches to address the current crisis in Ukraine through the convening of a Pan-Orthodox synaxis, or similar conciliar process, wherein an authentic solution can be found to this problem.

Our Metropolitan has called upon the Œcumenical Patriarch – by that descriptor – twice, in describing the ecclesial problem at hand. I tend to read this as a gentle term of rebuke: as though calling to mind a particular understanding of the oikoumenē as an imperial symbol. The Byzantines used it to refer to the ‘entire inhabited world’; that is to say, the world as inhabited by civilised (Roman) man. This oikoumenē no longer exists. That political reality is every bit as much gone as the Soviet Union now is. A new political ordo stands before us, and it is before this ordo that the Orthodox witness needs to be reformulated and rearticulated, otherwise we are condemned to our current ‘weakened witness’ in the ‘schism, antagonism and mutual division’ of the echoes of dead empires and the resurgence of duelling nationalisms and the spectres of fascism and ochlocracy. The current breach between the old imperial centre of Moscow and the older (and prouder) imperial centre of Constantinople is indeed saddening, but understandable. In this instance, though, if we were to choose between these two piles of gæopolitical rubble, Moscow has the clearer claim to right on her side than does Constantinople.

But just saying that eludes the greater question. What can revive that, or any, Orthodox witness? Only the practice of conciliarity, of sobornost’. Not just as a dreamy legacy of the long-dead Slavophils and populists. Not just as the anguished cry of the Russian Orthodox Christian intellectuals in diaspora. Not just as an academic buzzword to make fancy-pants Fordham professors and theology post-docs sound cleverer than they actually are. But as a real practice of sitting together in a spirit of truth, familial openness and respect. This has never been done, it bears saying once again, without an emperor. But we have no (shall we say œcumenical?) Constantine and no Justinian to turn to this time, who is willing to convoke all of the local churches on his authority, sit quietly to the side as they deliberate, and then meekly accept their consensus decision. We have no Ober-Prokuror Pobedonostsev this time to make the Bulgarians sit their butts down and behave themselves. This is a task that we, the Church, have to accomplish on our own. Lord, have mercy, and God help us all. Seriously.

It is said in recent days, both of ourselves and of our estranged brothers and sisters in the Roman Catholic Church, that we face massive and parallel crises of confidence. On its face, I wouldn’t dispute this. But such a characterisation I think misses part of the bigger picture. We are both dealing with self-inflicted wounds, precisely where our institutional praxis is weakest. Roman Catholics are struggling to maintain legitimacy in the eyes of their own faithful, precisely because their institutional structure is permanently locked into a rigid and almost militaristic defensive posture, such that they close ranks – almost literally – around even abusive priests. (One sees the same dynamic in, for example, American law enforcement.) We Orthodox Christians suffer from a problem that looks diametrically-opposite, but in fact shares similar features. When two of our hierarchs have a dispute, it isn’t hushed up and cordoned off within the hierarchy. We air our dirty laundry in public. We, as the saying goes, ‘take it outside’. We can’t help it. The conciliar and dialogical nature of Orthodoxy makes these differences of opinion – pardon the hideous turn of phrase, please – gloriously messy. But as the very legacy-imperial nature of these disputes shows, we’re no less militaristic and we’re no less prone to herd-thinking, wagon-circling and rank-closing; that is to say, the internal logic of these disputes is every bit as much the result of a deformed masculinity as that in the Catholic hierarchy is.

This is something we all will have to struggle with. The stakes – to put it litotically – aren’t exactly low, as Metropolitan Tikhon evidently fully comprehends. And in this case, it isn’t just the hierarchs and monks and clergy that are faced with the need to turn around. We all do. It may look like a weakness of our Church to a Catholic for whom the Holy Father in Rome provides the needed external security, or to a Protestant mystified by these frightening tides of mass mobilisation in seemingly-petty fights between bishops over centuries- and millennia-old ‘canons’. But the conciliar nature of our Church (including, as Vladyka Tikhon points out, the laity) can also be a source of strength – our ‘authentic solution’.

Save, O Lord, and have mercy upon our Most Blessèd Metropolitan Tikhon, His Grace our Bishop Paul, the priests and deacons and the whole clergy of thy Church, which thou hast established to feed the flock of thy Word, and by their prayers have mercy upon me, and save me, a sinner.

25 September 2018

Learning from Lossky’s Lancelot

Dealing with my Jennifer complex has not been a particularly easy thing. There’s a lot in it that’s probably more than a little unhealthy; but there is that in it which can, as my father confessor tells me, fertilise new growth. One of the books I had picked up, which Fr Paul encouraged me to keep reading, was a volume on Lancelot Andrewes, the Preacher: the Origins of the Mystical Theology of the Church of England by Fr Nicholas Vladimirovich (Lossky) – scion of Orthodox philosophers Nikolai Onufrievich Lossky and his son Vladimir Lossky who reposed last year. Now, Dr Lancelot Andrewes was familiar to me as one of the Caroline Divines and one of the great forefathers of the Anglo-Catholic socialism that had been so attractive to me in my college years. But I had never engaged as deeply with his work as I had with, say, Charles Gore or Frederick Denison Maurice, who seemed at any rate more ‘relevant’ to what I was thinking and doing in college. But now, after having swum the Bosporus and looking back on a journey that seems oddly parallel to a well-travelled historical route, I wonder if perhaps there isn’t something to learn from an old Englishman who ‘drew near’ the Greek Church Fathers as did Dr Andrewes. After all, what drew me to the Church of England in the first place was a movement of the heart, a movement toward beauty. And Dr Lancelot Andrewes would be the first to tell me, as would Fr Paul, that what has been required of me always – whether as an Episcopalian or as an Orthodox Christian – is not merely a turning ‘of the brain’, but rather a turning of the heart to Christ.

Fr Nicholas paints a broad-canvassed landscape painting of the theology of Dr Lancelot Andrewes that has four key ‘landmarks’. It is Incarnational; it is Patristic; it is Christological and Pneumatological in equal measure. Some of these landmarks can be spotted from afar in the brief biographical sketch he gives of Dr Lancelot at the beginning of the book: he notes Andrewes’ education in Syriac and Arabic (!) as well as Greek; lays special stress on the importance of the Church’s apostolic historical continuity to Andrewes; and highlights specifically the ‘intense interior life’ and the ‘theology lived in prayer’ which defined the spirituality of the first of the Caroline Divines. He also plays some defence for Andrewes: pointing out the common criticisms of Andrewes, court preacher to Queen Elizabeth I, King James (V)I and King Charles I, as a extreme absolute royalist and supine supplicant for King James (V)I’s favour, but then explaining how these criticisms are mitigated both by circumstance and by the balanced attitude Dr Andrewes himself took to the events in question (for example, the Essex-Howard divorce affair). He also treats Dr Andrewes’s uncharacteristically polemical exchanges with the Jesuit Cardinal Robert Bellarmine with a similar degree of understanding. But for the meat of the book, he looks to the sermons of Dr Lancelot Andrewes, and impressionistically paints the landscape as he goes by highlighting certain themes he returns to in his sermons at different occasions of the year and seasons of the Church calendar.

The incarnational Christology of Andrewes is central to understanding the rest of his work, and indeed the unity between public and private devotions that we see expressed in his life. Andrewes’ Christ is both God and a flesh-and-blood man; His birth is a historical event – indeed, it is the central historical event. Thus, for Andrewes, place and circumstance take on particular importance: for him Christ is not just any man. His parentage, His poverty, His location and His movements in history all obtain for Andrewes a deep significance for the way Christian theoria and praxis must both be done in the present. The poverty of Christ is the marker that He cares for the poor in our own age also – but it is also a marker of how far Christ has assumed human nature, how truly infinite in degree from the ineffable majesty of the Godhead are the sufferings which He bore for us from the beginning. Andrewes points to this with a ‘realist’ approach to Scriptural symbolism – the sense-objects and meanings which symbolise the holy are not merely markers. The logic, the logos of the Incarnation itself sanctifies these symbols, which participate and partake in the holy. The opposition between the awesome, insurmountable righteousness of God the Father, and the infinite and all-embracing mercy of God the Son, so keenly felt and yet never resolved within the puritanical religion of too many of the English reformers, for Dr Andrewes found a resolution in the person of Christ. The old dialectical problem, posed by Plato’s Socrates in the Protagoras, of the division and identity of the virtues, can be resolved only in a personal reality. For Andrewes, this personal reality is Christ Himself, who exemplifies, embodies and dynamically enacts through the Incarnation, the Passion and the Resurrection both Righteousness and Mercy, both Justice and Peace:

Christianity is a meeting, and to this meeting there go pia dogmata as well as bona opera—Righteousness as well as Truth. Err not this error then, to single any out as it were in disgrace of the rest; say not, one will serve the turn,—what should we do with the rest of the four? Take not a figure of rhetoric, and make of it a plain speech; seek not to be saved by Synecdoche. Each of these [Righteousness, Mercy, Justice, Peace] is a quarter of Christianity, you shall never while you live make it serve for the whole.‘Peace,’ indeed, ‘is a frequent concern of Andrewes’s,’ says Fr Nicholas. Christ as the Prince of Peace figures large in the landscape of his thought. Indeed, special stress is laid both on the insistence with which Andrewes lays hold of the Incarnational theology of the early Church Fathers (on which more later), and on the ways he would try to allude to the situation of the Church in England under monarchs beset by sedition, rebellion and foreign threat. In his sermons on peace, he was clearly addressing those who wield power – the sovereigns of England and Scotland. And it is in this light that we must see Andrewes’ detestation of military vainglory. Asks Andrewes:

What comes of this [lust for power]? Pacem contemnentes et gloriam appetentes, et gloriam perdunt et pacem: even this peace, their own part, they set light by; glory, God’s part, they gape after, and lose glory and peace both by the means; and when they have brought all to confusion, set down by their losses. For… by seeking glory, glory is lost.For Dr Andrewes, because the Incarnate Christ’s ministry was both public (His sermons on the mount, His feeding of the multitudes) and private (His teachings to the disciples, His withdrawals into the wilderness), so too should both the public and the private aspects of the individual Christian’s life be transfigured by Christ, to the point where the distinction disappears. Andrewes is a fervent English patriot and, yes, a royalist. In his sermons he likens the monarchs to Scriptural figures like Moses and David – the implication being that the Kingdom of England is a worthy successor to the Kingdom of Israel, and the Byzantine Empire. He can often come near to some disturbing conclusions in his work: for example, he is a steadfast supporter of the high justice of the king and the English state over the lives of criminals – that is to say, of the death penalty. Interestingly, he grounds this support for capital punishment in a theory that the criminal is radically responsible for his own sin; not society, not the state, not the devil and not God. Freedom of will is a visceral reality for Andrewes. As regards politics, Fr Nicholas is keen to point out that in terms of political panegyric, Andrewes is nowhere close to abasing his intellect or scraping before royal power to the degree that his continental contemporaries did. Two pillars exist for English rule, which he draws from the Psalms and likens to the British royal motto: Dieu et mon droit. God and justice. Woe to the English sovereign who ignores either.

Glory and Peace must be sung together. If we sing Glory without Peace, we sing but to halves. No Glory on high will be admitted without Peace upon earth. No gift on His Altar, which is a special part of His glory, but ‘lay down your gift there and leave it, and first go your way and make peace on earth’; and that done come again, and you shall then be accepted to give glory to Heaven, and not before.

Fr Nicholas Lossky notes that Dr Lancelot Andrewes can be justly accused of an extreme kind of royalism in his politics. This makes itself apparent in his exchanges with Cardinal Robert Bellarmine (with which Fr Nicholas does not treat), but also in his homiletics on various ‘political’ occasions – like 5 August (commemorating the conspiracy of the Gowries) and the 5th of November (remember, remember?). Dr Lancelot Andrewes could be strident, stern, even unforgiving, in his treatment of rebels and political subversives against the king. He exhorted his flock to give thanks for the destruction and deaths of John Ruthven and Guy Fawkes. Fr Nicholas Lossky acknowledges these faults in Dr Andrewes’s thinking and does not excuse them; instead he makes an argument for clemency. In addition to marking the ‘Byzantine’ character of these ‘political’ sermons, and their argument for the sacralisation of space and time and the consecration of the political sphere to the religious, he sees in these sermons no apologetic for tyranny – indeed, these declamations on the inviolability of the person of the sovereign are always counterbalanced with a reminder of the sovereign’s dependence on God’s grace and a stern admonition to the ruler not to trample upon God’s justice. He sees in these sermons ‘a theology of man, responsible for the cosmos’, in which even ordinary men and women are given a certain priesthood over creation for which they will be answerable to God.

But the Incarnational theology of Andrewes lends itself to yet another, more radical kind of political homiletics. Fr Nicholas points out that Dr Andrewes’s first sermons were preached against usury and in favour of the mediæval practice of tithing. Christ’s Passion, and indeed the parable of Lazarus and the rich man, are meant to call us to a remembrance of death. This remembrance brings to us an awareness of our earthly blessings, and urges upon us the need to seek both God and justice within this life, rather than awaiting the next in a spirit of complacency. ‘And of others not some other,’ Dr Andrewes preaches, ‘but Lazarus iste, one of those poor people whom we shun in the way, and drive our coaches apace to escape from; that of them, it may fall, we shall see some in bliss.’ The implication is clear: Christ having been born poor, Christ preaching among the poor, Christ living among the poor, Christ dying between two poor thieves – the kingdom of God belongs to the poor, and the rich enter it on their sufferance! This was a deep rebuke to the puritans. The riches we amass ‘here below’ are no sure sign of divine favour. Andrewes preached of hell to the rich during Lent; and he did so in a manner directly recalling St John Chrysostom. (It is easy to see where the ‘Anglo-Catholic socialist’ tendency found one of its main wellsprings.)

Dr Lancelot Andrewes, being conversant in the languages of the eastern Mediterranean, is notably a student of the Holy Hierarchs – Basil, Gregory, John Chrysostom – as well as the Desert Fathers and even Origen. For example, he uses the word ‘hypostatickal’ instead of ‘personal’ to refer to the nature of the Trinity and the union of the divine and human natures in the person of Jesus Christ. He resorts with emphatic and insistent frequency to the old Patristic formula: ‘God became man, so that man might become God.’ (To Dr Andrewes theōsis was not a foreign concept.) And he also places a great emphasis, particularly during the Lenten cycle, on the good works of the spiritual and ascetic disciplines, the fruits of the Tree of Repentance: ‘fasting, prayer and almsgiving’. His homiletic style is noted by Fr Nicholas to veer from the intellectual into something like poetry, and poetry at that resembling Byzantine hymnody. But it is St John Chrysostom who seems to exert the greatest ‘pull’ on the imagination and greatest influence on the homiletics of Andrewes, as seen above in his Lenten preaching on Lazarus.

Andrewes’ Lenten preaching in fact, during his own time, had certain links to the ‘mysticism’ of Saint Julian of Norwich (yes, she is a saint in my book), to the effect that his Patristic approach to the Incarnation led him to accentuate the joy and the eschatological hope implicit in the act of bringing to life of a dead human body from the grave. It is an overturning of the entire ‘natural’ order such as we understood it in our heathen blindness – and his preaching on the holy fear of the myrrh-bearing women at the tomb accentuates precisely the depth at which this overturning of nature struck the hearts of those who beheld it first, indeed went to the very depths of their hearts. The historical event of Christ’s life becomes, in His death and resurrection, ‘transhistorical’. Another order is established that will not pass away. The tears of Good Friday are turned at once into hosannas. It is hard not to hear certain echoes of the Golden-Tongue’s Paschal homily here:

Of all that be Christians, Christ is the hope; but not Christ every way considered, but as risen. Even in Christ un-risen there is no hope. Well doth the Apostle begin here; and when he would open to us ‘a gate of hope’, carry us to Christ’s sepulchre empty; to shew us, and to hear the Angel say, ‘He is risen.’ Thence after to deduce; if He were able to do thus much for Himself, He hath promised us as much, and will do as much for us. We will be restored to life.For Andrewes, Christ – Christ born among men, Christ baptised in the Jordan, Christ at the Last Supper, Christ crucified, Christ risen – is the centre, the core of all theology worthy of the name. It is to this that our minds are recalled, not only each year at Lent and Easter, but each time the Eucharist is received. Resurrection and remembrance (in the Christo-Platonic-cum-Greek Patristic sense) are imbibed each time we receive the Host, which is Christ Himself. Baptism and the Eucharist regenerate the state of man through this ‘remembrance’; they call man to himself (just as the prodigal son was called to himself in the parable), they enable man to repent, to turn around. Andrewes, as we have seen, stands firmly on the assertion of human free will, in the same way that Abba Cassian did, as did most of the Eastern Church Fathers. He avoids the charge of the heresy of Pelagius, levelled at him by puritan critics, precisely through his placement of Christ at the centre of his theology – but hidden within this ‘Christocentrism’, as Fr Nicholas terms it, is also a ‘Pneumatocentrism’: the freedom of man is a gift of the Holy Ghost. Fr Nicholas sums up Andrewes’ view thus: ‘Man’s only true vocation… is union with God in Christ through the Holy Spirit.’ And this participation, this union, is achieved only through the exercise of freedom in repentance and in the ascetic disciplines. The perspective changes from season to season: the redemptive logic of the Incarnation beheld in the Nativity, though complete, becomes dynamic, active, effective in the Passion and Resurrection.

Fr Nicholas demonstrates quite adroitly how all of these aspects of Dr Andrewes’s theology – his Incarnationalism, his Patristic emphasis, and his placement of Christ and the Holy Spirit at the core, at the heart, of his spiritual life, as the way to participate in the life of the Father – support and reinforce each other in a way reminiscent of, even where not directly owing to, the Byzantine theological tradition. This volume is not mere wishy-washy ‘œcumenical’ thinking; not a hare-brained ‘grand project’ to show how, because Anglicans and Orthodox Christians believe some of the same things, that we are fundamentally alike. This carefully-researched portrait of an Anglican Divine’s spiritual life and theological contributions to the English tradition, painted by a Russian-French priest of the Orthodox Church, is much more modest in its scope. Not being a vanity project, therefore, I found it both touching in its sympathy and surprising in its depth. I came away from this book with both a much deeper awe and respect for Dr Lancelot Andrewes; with a much deeper – maybe healthier? – appreciation for the roots of the ‘Anglo-Catholic socialist’ tradition for which Andrewes sowed the seed; and also, unfortunately, with a distinct sadness for the comparative paucity of modern Episcopalian praxis.

One of the great things about the Episcopalians is their discernment for beauty, and this is certainly something that I still treasure. After all, my own intellectual formation was shaped and ‘tuned’ by certain erotic facets of my own heart. Among the Protestant formations the Anglican Communion is the one that best approached an understanding of Dostoevsky’s maxim that ‘beauty will save the world’. One sees the same understanding of beauty in Dr Lancelot Andrewes’s theology as presented here: he is able to take the theological poetry of the Church Fathers and craft a similar symmetry within his own homilies. But there is something in Andrewes’s work that goes beneath the surface, and touches the hidden depths of the person. His Incarnational, Patristic Christology and his theology of the Holy Spirit actively seek out where the prodigal son lingers in his self-imposed exile. It seeks to show the reality of the tomb, and the way in which Christ can overturn that reality and transform that tomb of our heart into a place of resurrection.

I can see in part why my father-confessor encouraged me to read this book. (Of course part of it was that Fr Paul attended lectures by Fr Nicholas Lossky, and has immense personal respect for the man.) Fr Nicholas treats with a ‘Byzantine’ image of Dr Lancelot Andrewes. He presents to us an interpretation of Andrewes’s work in depth rather than in a watered-down form, and he presents us with an image of an English clergyman steeped in Greek, Syriac and Arabic theological learning, concerned with man in his depths, in the heart which is infinite in its depths.

Labels:

Anglican Communion,

Anglophilia,

books,

Britannia,

Elláda,

La Gaule,

lefty stuff,

personal,

philosophy,

politics,

Pravoslávie,

Toryism

24 September 2018

月餅節快樂!

A happy mid-autumn festival to one and all!

I confess I have little worthy of blogging to offer on this occasion, but please feel free to enjoy my folkloric-Chestertonian musings from last year along with your mooncake. Cheers!

22 September 2018

‘Rustic’ poetry, simplicity, attraction of the mind

喓喓草蟲、趯趯阜螽

未見君子、憂心忡忡。

亦既見止、亦既覯止、我心則降。

陟彼南山、言采其蕨。

未見君子、憂心惙惙。

亦既見止、亦既覯止、我心則說。

陟彼南山、言采其薇。

未見君子、我心傷悲。

亦既見止、亦既覯止、我心則夷。

The meadow grasshopper chirps

And the hillside grasshopper leaps.

Until I have seen my lord,

My anxious heart is disturbed.

But as soon as I shall see him,

As soon as I shall join him,

My heart will have peace.

I climb that southern hill

There to gather the ferns.

Until I have seen my lord,

My anxious heart is tortured.

But as soon as I shall see him,

As soon as I shall join him,

My heart will be gay.

I climb that southern hill

There to gather the ferns.

Until I have seen my lord,

My heart is troubled and sad.

But as soon as I shall see him,

As soon as I shall join him,

My heart will be soothed.

- The Odes 《詩經》, Caochong 《草蟲》, Shao and the South 召南 3

爰采唐矣、沬之鄉矣。

云誰之思、美孟姜矣。

期我乎桑中、要我乎上宮、送我乎淇之上矣。

爰采麥矣、沬之北矣。

云誰之思、美孟弋矣。

期我乎桑中、要我乎上宮、送我乎淇之上矣 。

爰采葑矣、沬之東矣。

云誰之思、美孟庸矣。

期我乎桑中、要我乎上宮、送我乎淇之上矣。

Where does one pick the dodder?

In the country of Mei.

Know you of whom I am thinking?

The beautiful Meng Jiang.

She waits for me at Sangzhong;

She yearns for me at Shanggong;

She follows me on the Qi!

Where does one pick the wheat?

On the north side of Mei.

Know you of whom I am thinking?

The beautiful Meng Yi.

She waits for me at Sangzhong;

She yearns for me at Shanggong;

She follows me on the Qi!

Where does one pick the turnip?

On the east side of Mei.

Know you of whom I am thinking?

The beautiful Meng Yong.

She waits for me at Sangzhong;

She yearns for me at Shanggong;

She follows me on the Qi!

- The Odes 《詩經》, Sangzhong 《桑中》, Airs of Yong 鄘風 4

溱與洧、方渙渙兮。

士與女、方秉蕑兮。

女曰觀乎。

士曰既且。

且往觀乎。

洧之外、洵訏且樂。

維士與女、伊其相謔、贈之以勺藥。

溱與洧、瀏其清矣。

士與女、殷其盈兮。

女曰觀乎。

士曰既且。

且往觀乎。

洧之外、洵訏且樂。

維士與女、伊其將謔、贈之以勺藥。

The Zhen and the Wei

Have overflowed their banks.

The youths and maidens

Come to the orchids.

The girls invite the boys: ‘Suppose we go over?’

And the lads reply: ‘Have we not been?’

‘Even so, yet suppose…’

‘… we go over again.’

For over the Wei,

A fair green-sward lies.

Then the lads and the girls

Take their pleasure together;

And the girls are then given a flower as a token.

The Zhen and the Wei

Are full of clear water.

The lads and the girls

In crowds are assembled.

The girls invite the boys: ‘Suppose we go over?’

And the lads reply: ‘Have we not been?’

‘Even so, yet suppose…’

‘… we go over again.’

For over the Wei,

A fair green-sward lies.

Then the lads and the girls

Take their pleasure together;

And the girls are then given a flower as a token.

- The Odes 《詩經》, Zhen and Wei 《溱洧》, Airs of Zheng 秦風 21

‘Food and sex – that’s what people want. Shi se xing ye 食色性也.’ That’s what my wife said to me with a laugh – quoting an idiom coined by Gao Buhai 告不害 (one of the zhuzi baijia 諸子百家) in the Mencius, who in turn was paraphrasing the Classic of Rites 《禮記》 – as I told her that I was reading the Granet-Edwards translation of the Classic of Odes 《詩經》. (I left out the part about how I was basically provoked into reading it by the eldest of the theological Hart brothers, the same one who made me a fan of comedian and documentarian Rich Hall.)

Now, this being a translation, I am sensitive that I am pretty much wholly at the mercy of Granet and Edwards – a French sociologist, looking at these poems through an anthropological lens, and his English translator – and their interpretations. The validity of all of what I write below must be tempered by that understanding. But Granet argues, rather convincingly, that the Odes are basically a collection of folk songs; folk songs that describe and speak to the realities of life in the villages and countryside of China in deep antiquity.

Granet – being a good sociologist – draws a number of conclusions from these songs that attempt to paint a vivid portrait of village and country life in China’s deep antiquity. Granet seems given to certain orgiastic flights of fancy that seemingly tell us not so much about ancient Chinese culture as they do a bit more than we need to know about his imagination (a common enough failing among sociologists of a particular Freudian era). But more valuable are his comparisons of archaic rural Chinese betrothal and marriage festivities with the customs of their neighbours: the Yi, the Pubiao and the Hmong. Granet puts forward lively images of bands of young men and young women from different villages (exogamy being strictly upheld) meeting together at a carefully-determined date in springtime, just after the winter thaw, at festivals and fairs held at sacred sites like the confluences of two rivers, a copse or a hillside, giving each other gifts, holding competitions with each other in choral singing, sports and racing, and then pairing off to court each other for the remainder, before the festival ended and they returned to their home villages – to be married off to their chosen partners the following autumn. To my mind there is something very charming in a McTellian way (also) about these images, and that’s probably no accident – the folk tradition being what it is.

From a literary view, these folk songs, even in translation, are simple. They spring forth from a singleness of mind. They contain little by way of characterisation, few metaphors and certainly nothing by way of extended conceits; they rely on repetition, antiphonal structure and rhythm for their power. But they are powerful: touching, indeed in many cases stirring – due in part to their frank directness. They speak to deep needs, desires, passions in the human heart. They are concerned with the stuff of a peasant’s daily life: harvesting, gathering wood, hunting, eating, sleeping, the rise and fall of the rivers, the turn of the seasons. They are concerned even more with courtship and erotic love. The first awkward, halting, sometimes confrontational – but seasonal and heavily ritualised – meetings between boys and girls of different villages. The awakening of desire. The heartaches and anguish of first love and parting. Loneliness. The thrills of the chase and the plight of covert assignations. The dread and sorrow (for a girl) of leaving her parents and siblings for a new village. The bliss of consummation. Heartbreak. Despite the lack of personal details – very few of the characters have names, and even those that do are generic enough to avoid causing scandals for the young folk involved – the Odes speak to something deeply human that are easy for those who have loved to recognise.

These poetic expressions, as you can see from the Yong ode ‘Sangzhong’ which I’ve quoted above, are deeply laden with gæographical and botanical imagery, but there is nothing really symbolic in them; rather, they reflect and amplify the emotions expressed within them. Granet calls these ‘rustic themes’. He says:

It is evident that the odes of the Shih ching frequently contain lively and sparkling descriptions of subjects borrowed from Nature … Sometimes we are shown a tree in the fullness of its vigorous growth, and, when its flowers, fruit, leaves and branches are praised, it seems that a parallel is being drawn between the growth of plants and the awakening of the human heart … the loves of the beasts seem to be the counterpart of those of men. The state of the weather, the thunder, snow, wind, dew, rain and the rainbow, or the crops, the gathering of fruits or herbs also form a frame or an opportunity for the expression of the emotions.Granet includes in his translation the traditional interpretations of the compilers and scholastic commentators of the Odes, including most importantly Mao Heng 毛亨 and Zhu Xi 朱熹. But he clearly takes issue, often quite disparagingly, with the scholarly hermeneutic they apply to the texts: in the broad strokes, he finds these classicist commentators too eager to twist the simple, innocent expressions of feeling in the Odes into sophisticated satires on the policies of the feudal lords of the various states from which the Odes were collected, or else examples of or warnings against the deterioration of morals and feudal ritual propriety in ill-governed states. The irony, of which Granet appears sensible enough himself, is that Confucius himself would probably agree more with him, Granet, than with his own mediæval followers. From the Analects:

子曰:「詩三百,一言以蔽之,曰『思無邪』。」(What a far cry indeed from Zhu Xi’s interpretations, which are so apt to see depraved thoughts and licentiousness at each turn in the Odes!)

The Master said, ‘In the Book of Poetry are three hundred pieces, but the design of them all may be embraced in one sentence: “Having no depraved thoughts”.’

But clearly, even though Confucius himself thought some of the Odes to be ‘lewd’ (like those belonging to the state of Zheng), he found certain of them worthy of being kept in this collection – and this has always been something of a puzzlement to the later compilers. As Granet puts it:

The embarrassment of the Chinese tradition is evident. It may be expounded thus: after the Shih ching was used as a theme for exercises in rhetoric, and especially after it had become a classic and a subject of instruction, it was considered desirable to attribute to this educational work a moral value, independent both of the use to which it might be put and of the value which it would have had from the beginning. The odes were used for purposes of instruction and it was imagined that they were composed for that purpose…Now, from my own perspective, since (as I am not a ‘higher critic’) there is no valid internal reason to doubt the Chinese tradition which holds Confucius to have been the compiler of the Odes, the challenge for Confucians posed by Granet is evident. Why did Confucius, who placed such peculiar emphasis on the importance of the Odes for understanding his teachings (to the point where he would not teach even his relatives who hadn’t read the Odes), include these ‘sensual’ songs? Granet nowhere alludes to this comparative-philosophical point, but I will draw the connexion explicitly. By including the love-songs of Zheng (like ‘Zhen and Wei’ above) in the Odes Confucius poses to Chinese society the same challenges about the nature and purpose of poetry that Socrates poses to the Greeks about Homer’s Achilles in Plato’s Dialogues, particularly the Hippias Minor and the Republic.

But for the moral which was to be inculcated some of the songs seemed too licentious; it was felt that they were not adequately excused by saying that the presentation of vice recalls to virtue—for tradition declared them to be licentious. Fortunately, opinion declared the expurgation of the Shih ching by a Sage, and that made it possible, since, officially, no licentious poems were to be found in the collection, to put forward for most of the poems an interpretation which rid them of all baleful influence by completely setting aside their character as love-songs. But in some instances, this method was defective, and it had to be admitted that a certain number of sensual poems were included in the Shih ching.

The Odes themselves ‘have no depraved thoughts’; so says Confucius in the Analects. But why would he say this when these love-songs – direct, bold, sometimes even ‘indecent’ by the Sage’s own standards – would offend both contemporary and later ritual-moral sensibilities? Granet notes:

No mere declarations and tokens of love sufficed to bind [young lovers’] hearts that demanded nothing less than that complete union which would give them eternal possession of each other. It is not to be wondered at that, in songs in which Chinese commentators see only licentiousness, foreigners find traces of an ancient morality, preferable to the existing one. This is due to the fact that, in the lavish protestations of faithfulness made by the lovers, they see an ancient monogamy. As a matter of fact, from the time of their union in the festival of general harmony the lovers considered themselves bound irrevocably, and their apprehensions and agony gave place to security and peace of mind.Reflecting on which I would ask, in all seriousness: is it so hard to believe that Confucius himself might have seen the Odes in a similar way as Granet (and the ‘foreigners’ he references) claims to? After all, the Analects are not lacking in praise for simple, direct ceremonies and music (!), particularly those found in elder times, and particularly in comparison with the elaborateness and subtlety of the prevailing ritual norms of his own day. (And he particularly detested toadies with well-kept appearances, insinuating manners, glib tongues and fine, well-honed speeches.)

子曰:「先進於禮樂,野人也;後進於禮樂,君子也。如用之,則吾從先進。」And then there is this instance in which Confucius references the Odes directly, talking about them with his student Bu Zixia 卜子夏:

The Master said, ‘The men of former times in the matters of ceremonies and music were rustics, it is said, while the men of these latter times, in ceremonies and music, are accomplished gentlemen. If I have occasion to use those things, I follow the men of former times.’

- The Analects 《論語》 11.1

子夏問曰:「『巧笑倩兮,美目盼兮,素以為絢兮。』何謂也?」子曰:「繪事後素。」曰:「禮後乎?」子曰:「起予者商也!始可與言詩已矣。」To what, precisely, did Bu Zixia find the ceremonies (or li 禮) subsequent – that is to say, contingent or dependent upon? The Analects answers this question, too. And note this: the answer carries a direct reference to the Odes:

Zi Xia asked, saying, ‘What is the meaning of the passage – “The pretty dimples of her artful smile! The well-defined black and white of her eye! The plain ground for the colours!”?’ The Master said, ‘The business of laying on the colours follows (the preparation of) the plain ground.’ ‘Ceremonies then are a subsequent thing?’ The Master said, ‘It is Shang who can bring out my meaning. Now I can begin to talk about the Odes with him.’

- The Analects 《論語》 4.8

子曰:「興於詩,立於禮。成於樂。」The Odes, then, were not meant to ‘establish character’ or to provide ‘finish’ to a student’s education. It appears that Confucius did not mean to use them as a guide to the establishment of good character and good ritual norms in a civilised state (the two of those being suspended in a certain dialectic): that’s what the Book of Rites was for. The Odes, rather, are meant to ‘arouse the mind’ (xing 興 – a term which can also be glossed as ‘interest’, ‘wonder’, ‘excite’, ‘pleasure’; whose gloss of ‘arouse’, interestingly enough, also includes erotic entendres; and which, to me, recalls in particular the Platonic use of aporia). What does Confucius mean for us to be excited by, or to wonder at, in the Odes? I wonder if it is not precisely what foreigners wonder at in them.

The Master said, ‘It is by the Odes that the mind is aroused. It is by the Rules of Propriety that the character is established. It is from Music that the finish is received.’

- The Analects 《論語》 8.8

We see, after all, a number of things in the Odes, that are the subject of exuberant (though unpolished) expression. The patterns of the seasons. The often-terrifying majesty of thunder, rain, wind and floodwaters. Awe at natural beauty – in lakes, hills, rivers, trees, flowers. Delight in the form of a young woman from a man’s perspective. Delight in the form of a young man from a woman’s perspective. Mystique – half-rejection, exhilarated pursuit, gossip, attraction, flirtatiousness, abandon – in the seasonal meeting of the two sexes, separated by custom, by gæography (exogamy, remember?), by the primoridal order of the cosmos. What is seen in the Odes are man’s erotic – in the full breadth and depth of the term – stirrings upon beholding the face of the Divine. It is in this vein also that a devotee of Confucius in the ‘foreign’ land of Chu, Qu Yuan 屈原, wrote the Chuci 《楚辭》. ‘Shi se xing ye’ is not a dismissal. Confucius talked about the superior man returning to the root. He would have us behold all of this and wonder at man’s condition, wonder at his place in the cosmos. If we do not have a good ‘plain ground’, how can we apply bright colours? If we do not understand and respect the human appetites, how can we possibly understand the need for rites? If we do not look on the human condition and love it, and feel compassion for it, how can we possibly begin to seek to correct that condition in ourselves?

In a certain sense, I am beginning to suspect that Zhuangzi 莊子 had it right – at least partially. Much like Khomyakov and Herzen in Russian intellectual history, Confucius and Laozi 老子 were probably closer to each other in outlook than either of their respective students and schools ever would be afterward in history, despite the efforts of syncretic thinkers like Dong Zhongshu 董仲舒 and Wang Bi 王弼 who tried to bridge the two schools of thought. Confucius and Laozi beheld the same human Dao. The two of them shared a certain awe of it. Confucius placed the emphasis on the ‘human’ and followed the Odes. Laozi placed the emphasis on the ‘Dao’ and followed it – out of China. But that is a reflection, perhaps, for another time.

One final thought. If Confucianism is ever going to be made relevant again in an uncertain age such as this, perhaps one of the things that will be demanded of the academic proponents of Confucianism is that they find creative ways to recapture the simplicity and singleness of mind in the Odes, and have us wonder at them.

Labels:

Adam and Eve,

Anglophilia,

Britannia,

Confucianism,

culture,

Elláda,

folk rock,

history,

Huaxia,

La Gaule,

Mueang,

music,

philosophy,

poetry

21 September 2018

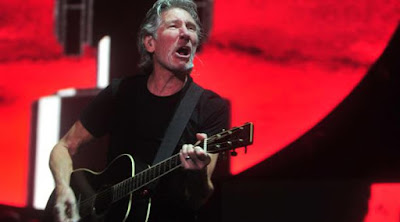

The piper at the gates of Don?

Huh. The mayor of Sevastopol is now a Pink Floyd fan. Go figure. Of course, former President of Russia Dmitry Medvedev is a fan of Deep Purple, so perhaps that shouldn’t be so surprising.

Still: Mr Waters does have a good historical point about Sevastopol and Crimea. Just as he had a point about the Maidan and Yanukovych more generally. Just as he has a point to make about Palestine. Just as he has a point about Syria and the White Helmets. Just as he has a point about our current political leadership class in general. To Roger’s credit, his recent pronouncements are of a piece with a long history of anti-war sentiment expressed both in music and in interviews, compassing the Falklands War, the Yugoslav Wars and the Iraq War, at the very least.

Perhaps it is rare to see a rock star with this kind of consistency? In any event, sir, kudos.

Labels:

Anglophilia,

Britannia,

Holmgård and Beyond,

international affairs,

Levant,

metal,

music,

politics,

prog rock

18 September 2018

Iov (Kundria) the Venerable of Ugolka

Ten years ago today, the canonical Ukrainian Orthodox Church canonised the holy Carpathian-Rusin Archimandrite Iov, who was the monastic head of the Eparchy of Khust and Vinograd. A gentle monastic under the Soviet authorities, he nevertheless stood fast against incursions by the government, for the traditional rights of Orthodox monasteries and the Church more generally. Many thanks to Fr Edward (Pehanich) for writing the life of this recent saint of Carpathian Rus’, from which I borrow heavily here!

Ivan Georgevich Kundria was born in the small Rusin village of Iza under the (often cruelly oppressive) Habsburg Monarchy, one of eight children in his family. He attended the local public school and graduated in 1920 with a specialisation in agronomy and animal husbandry. (Iza, it should be remembered, was the village where the return of the Rusins to Orthodoxy from Uniatism had begun in earnest, at the behest of priests returning from America who had served under Fr Alexis of Wilkes-Barre.) By the time he graduated, Iza had been integrated with the rest of Transcarpathia into the First Czechoslovak Republic, and young Ivan Georgevich joined the Czechoslovak Army, serving with distinction and loyalty in a unit stationed in Michalovce. Young Ivan saved up some money, and after his term of service, he twice made the journey on foot to Mount Athos, but was refused admission to the Russian Monastery of St Panteleimon there because he did not have the proper paperwork, and the Greek government was at that time legally restricting the number of non-Greeks allowed to live on the holy mountain.

Ivan Kundria attended the school at the Monastery of St Nicholas in his home village and graduated from there with a degree in pastoral theology. He and his brother the Hieromonk Panteleimon (Kundria) pooled everything they had and used it to buy a plot of land in the neighbouring village of Gorodilovo, on which was to be built a monastery consecrated, after the example of the monastery founded by St Sergius of Radonezh, to the Holy Trinity. The funds for the building were provided as a gift from St Panteleimon’s Monastery on Athos, as well as a relic from Greatmartyr Demetrius the Myrr-Streaming of Thessaloniki. The first rector of this monastery was the Venerable Saint Aleksei (Kabalyuk) of blessed memory, from whose loving and patient hands Ivan Kundria received the tonsure and the monastic name of Iov, on 22 December 1938.

Monk Iov’s life at the Holy Trinity Monastery was soon to suffer great sorrow and disruption. The Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939, and the Rusin people of Transcarpathia were driven en masse into the Soviet Union. They went in great processions, often preceded by their crosses and icons, along with what few meagre worldly goods they had, piled onto rickety carts. Unknowingly, they were fleeing toward – not a welcoming country of kinsmen, but a ruthless and determined atheist persecutor, the revolutionary Soviet government which had come to power more than twenty years before. Stalin had many of these Carpathian Rusins rounded up, arrested and sent straight on to Siberia when they came over the border from Czechoslovakia and Poland into Russia – and many of them perished en route or died of starvation once they arrived. Those Stalin could conscript for his armies, he did, and Monk Iov (having served in the Czechoslovak Army) was one such conscript.

Monk Iov was sent by the Soviets to the front lines to fight Hitler and the Nazis as an artilleryman in the First Czechoslovak Army Corps under Lieutenant-Colonel (later General) Ludvík Svoboda. As a monk, he was forbidden from shedding blood; when ordered to fire mortars, he would defuse them in secret before loading and firing them so that they could do no harm. It was during his service in the army that he met Archbishop Saint Luke (Voino-Yasenetsky) of Krasnoyarsk; the saintly doctor apparently made quite an impression on the younger Rusin monk, and all the rest of his life Saint Iov kept a photograph of him in his cell in a place of honour, alongside that of Gen Svoboda. For his service in the war, Gen Svoboda honoured him with a position as a Czechoslovak Embassy guard in Moscow – and later was secured pardon from his Siberian sentence by Gen Svoboda and given leave to return to Holy Trinity Monastery.

He was very quickly appointed to the priesthood and later made abbot at Gorodilovo, and served the Liturgy every day with prayerful attention. He set an example of humility, and did the menial work of the monastery alongside his brothers. His spiritual children, both inside and outside the monastery, benefitted greatly from his meek, kindly and merciful disposition, and he was greatly loved by all around him.

Fr Iov’s difficulties continued, however – the Soviets appointed a ‘bishop’, Barlaam, whose mission it was to close and liquidate the monasteries in Transcarpathia; Holy Trinity at Gorodilovo was not exempt – particularly when Fr Iov complained of Barlaam’s tyranny to the Patriarch in Moscow. He was sent from monastery to monastery after that, and in 1962 he ended up in the small Rusin village of Monastyrets (Mala Ugolka or Little Ugolka), at a hram dedicated to Greatmartyr Demetrius of Thessaloniki. Legend had it that Monastyrets was where the disciples of Saint Methodius fled after being forced out of Velehrad by hostile German authorities.

Fr Iov won the hearts of the people of Little Ugolka through an example of hard work, patience and humility that soon earned him the reputation of a starets. He served the Liturgy every day, just as he had at Gorodilovo. He made predictions about the end of Communist rule (that would come to be proven true after his repose), healed the sick, gave spiritual advice to many from peasants to university professors, and especially delighted in match-making for young couples. It is said that no marriage that had been arranged and blessed by him ever ended in divorce. During the 1960s he presided over the consecrations of over thirty temples and monasteries in the Carpathians.

He reposed peacefully on the 28th of July, 1985, and was soon considered for glorification, as the healing miracles continued even after his death. His relics – his body, Gospel, cross and vestments – were all found to be incorrupt, and smelled of myrrh and incense when they were unearthed. His relics were then placed in honour in the Church of Saint Demetrius at Little Ugolka, the town to which the Soviets had exiled him but which he nonetheless made his home. Holy Father Iov, Venerable Abbot and Wonderworker, pray to Christ our God for us, your unworthy children!

Labels:

Blue Europa,

Elláda,

history,

Holmgård and Beyond,

Pravoslávie,

prayers,

Sibiir,

Teutonia,

Velká Morava

17 September 2018

Remembering Sabra and Shatila

On 16 September 1982, about 150 members of a right-wing fascist paramilitary affiliated with the Uniate (Maronite) Phalange in Lebanon, entered the Palestinian refugee camp at Shatila and the Beirut neighbourhood of Sabra with the express blessing of the Israeli Defence Forces. Immediately, they began waging a sadistic, brutal campaign of ethnic cleansing – torture, rape, mutilation, murder – of the Palestinian refugees and Lebanese Shia Muslims who lived there. Their victims were mostly women, children and elderly civilians: somewhere between 1,000 and 3,500 innocent people (the exact figure is still unknown, though the higher one is likely) perished at the hands of the Phalange, while the Israeli armed forces watched and did nothing to prevent it. It was the single bloodiest event of the conflict between Israel and the Arab world, and is still remembered as a war crime in which the Israeli and American governments were complicit.

The ostensible reason for this horrific bloodbath was the assassination of the leader of the Phalange, Bachir Gemayel. They believed that a member or sympathiser of the Palestine Liberation Organisation was responsible; however, when the dust cleared the assassin turned out to have been a member of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party instead. In fact, the actual culprit did not matter. The bloodthirst of the Phalange has roots deeper in history. It is arguable – as William Dalrymple does, for example – that the more fanatical followers of the monothelite heresiarch Marun have been waging war against their neighbours since the Council of Chalcedon. They made the best of the Crusades by acting as native informants for the French, and eventually joining the Catholic Church in 1181 – the first instance of uniatism in Eastern Christian history. There is certainly something more to be written at a later date, for the ease with which Uniate Catholicisms adopt far-right racist and fascist ideologies like that which the Phalange promoted. But in the case of Sabra and Shatila, the ideology was a veneer and a ready excuse to indulge a deeper cultural hatred of the Syrian Arabs and the religious beliefs they represented – both Islamic and Byzantine Christian.

However, what the Phalange did to the Palestinian people in 1982 simply could not have been accomplished without the direct support of the Israeli armed forces, and the duplicity of the Reagan administration in dealing with the Arab leadership. Israel – particularly the Likudniks and the military hard-liners under Ariel Sharon – had been planning an invasion of Lebanon for a long time in order to root out the PLO, and they would have done so anyway even if the Maronites had not offered themselves as accomplices in that action. And when the massacre did occur, the Israeli army used flares to aid the Phalange in its bloody business, and also blocked off all routes leading out of West Beirut and from the Shatila refugee camp so that the Palestinians could not escape. When the Phalangists had finished their work, the Israeli armed forces furnished the bulldozers that allowed them to pile the bodies in mass graves.

Our own government was very far from innocent. The Reagan government had brokered the ceasefire which the Israelis broke when Bachir Gemayel was assassinated. One of the terms of that ceasefire was that Palestinian civilians like those in the Shatila camp and those in Beirut would be protected from violence after a PLO withdrawal. Of course, without the PLO, the Palestinians had no one to guarantee their safety, no one to advocate for them or vouch for them or protect them. They provided the perfect scapegoats for the Phalange – who calculated their massacre in the full knowledge that they wouldn’t face any sort of retribution from the authorities who brokered the ceasefire. The United States would not materially oppose Israeli interests in Lebanon, and certainly not to defend a few camps full of stateless indigents.

I had only just graduated from college when I saw Waltz with Bashir. I actually don’t remember the film all that well – I only remember the newsreel clips of Sabra and Shatila in the aftermath. The blood and the bodies in the streets. The mutilated limbs, the charred flesh, the weeping elderly women. But not only on film – it is a crime still within living memory, and the Palestinians still remember it with sober grief. Palestine must be free, if the innocent human beings murdered at Sabra and Shatila are ever to rest in peace.

EDIT: Today in the OCA we also commemorate the 156 Martyrs of Palestine, Christians of Egypt and the Holy Land who suffered under the persecutions of the pagan Roman Emperor Maximian Galerius in the fourth century AD. For your long-suffering people, O Holy Peleus, Nilus, Zeno, Patermuthius, Elias and your laudable Fellow Sufferers, intercede with Our Lord Christ for their salvation and ours!

16 September 2018

Holy Martyr Ludmila of Tetín

Ludmila, Protomartyr of the Czech people and a South Slav by origin, was the wife of Kníže Bořivoj of the Czech lands. Bořivoj, who belonged to the pagan noble Přemyslovci, was baptised along with his wife Ludmila by Holy Father Methodius, Enlightener of the Slavs, in his evangelical mission to that people. Both husband and wife took to their new faith with the zeal of the newly-converted, and began supporting churches and inviting priests to hold Divine Liturgy among the Czechs.

Unfortunately, Bořivoj died in 889, leaving Saint Ludmila a widow at the young age of twenty-eight. Their sons, Spytihněv and Vratislav, succeeded their father to the office of Kníže, and Saint Ludmila assisted them as she could – though the young widow never remarried. Instead she devoted her life to prayer.

Vratislav married a pagan woman named Drahomíra, with whom they had a son who would become a saint in his own right: Martyr-Duke Václav the Good. Saint Ludmila was charged with the young child’s upbringing. She doted on young Václav, and made sure he was provided with a good education, sending him to the church school in Budeč. When Kníže Vratislav died, his wife Drahomíra assumed the regency for her son, who was then still only eight years of age. Drahomíra, jealous of her mother-in-law’s influence over Václav, began influencing the young Kníže to allow pagan practices among the Czech people.

Saint Ludmila objected – vehemently, and Drahomíra seized the opportunity to begin laying plans to have her murdered. When Ludmila retired to her home in the town of Tetín, Drahomíra sent after her two retainers, who burst in on her at home and strangled her with her own veil. Practically at once after the news of how the Martyr Ludmila died spread, she began to be venerated as a saint among Czech Christians. She was buried in the local church at Tetín, but her remains were later translated to the Basilica of St. George in Prague.

Holy Martyr Ludmila is remembered today on the Orthodox New Calendar, along with the Synaxis of Saints of Carpatho-Rus. Among the saints most important to the long-suffering Rusin people, Protomartyr Ludmila is honoured alongside Saints Cyril and Methodius, Holy Prince Rastislav, Martyr-Duke Václav, Venerable Prokop of Sázava, Venerable Moses of Kiev, Venerable Efrem of Novotorzhsk, Holy Father Alexis of Wilkes-Barre, Saint Aleksei of Khust, New Priestmartyr Maksim of Gorlice and New Hieromartyr Gorazd of Prague.

Ludmila, martyr for the True Faith and holy grandmother of the Czech people, pray to Christ our God that the souls of us, your wayward children, may be saved!

O Ludmila, when godly fear entered thy heart,

Thou didst abandon the glory of the world,

And hasten to God the Word.

Thou didst take His yoke on thy flesh,

And shed thy blood in a contest surpassing nature.

O glorious Martyr, entreat Christ our God to grant us His great mercy!

Labels:

history,

Holmgård and Beyond,

Illyria,

Pravoslávie,

prayers,

Velká Morava

15 September 2018

The Platonic Tory feminism of Mary Astell

I have made mention once or twice of Mary Astell on this blog before, but have only seriously engaged with her work recently. In fact, I’m rather glad I did – A Serious Proposal to the Ladies would hardly make as much sense if not regarded in its true Platonic light. I’m also indebted to several other comparisons to her work which I could not have made when I first became aware of Astell’s contributions to Western philosophy.

Mary Astell, whose proposal for a religious retirement for women of all ages desirous of education or spiritual improvement unfortunately fell on the ears of an English male public more inclined to toss cheap wit at it than to take it seriously, was hardly a political radical in her own day. She was certainly a Tory of the old-fashioned make. She believed wholeheartedly in the supremacy of the English crown and was avid in her defence of royal prerogatives. As her Serious Proposal shows, she was a devotee of traditional High Church Anglicanism (complete with its clerical hierarchies, elaborate liturgics and fasting and feasting observances), and even some male readers otherwise sympathetic to her thought her proposal for a ladies’ religious retreat to be something too ‘popish’ and too akin to continental monasticism to be taken seriously. She hated the ‘upstart’ pretensions of the new moneyed class, and saw them as a threat to the ethos and privileges of the elder nobility. And she had that distinctively-Tory detestation of mercantile greed and capitalism that characterised people like Abp William Laud, Fr Jonathan Swift, and the later Dr Samuel Johnson, Robert Southey and Richard Oastler. But the natural comparison which my mind is most wont to make, is that between Mary Astell and Ban Zhao 班昭, the historian, Old Text philologue and advocate of women’s education who wrote her Lessons for Women 《女誡》 during the Later Han Dynasty in China.

Astell’s own advocacy for women’s education in England has a philosophical dimension and a religious one. Philosophically, she draws heavily upon Plato. She makes explicit mention of Socrates and the Socratic method in A Serious Proposal, but more specifically, she appeals to Platonic tradition of ‘forgetting the body’ temporarily, and establishes through such argumentation that the poor state of women’s development in her own day is owing to lack of education rather than a natural or inborn defect. Women are as capable of transcending themselves and their baser passions as men are. She then lays out a plan for the improvement of women’s souls through careful religious education; devotion to God through prayer, fasting and attendance at Church services; and cultivating close friendships with other women engaged in the same disciplines. She also uses an appeal to men that comes straight from the Phædrus. The ‘true lover’ of a woman, she argues, is one who will respect her and encourage the cultivation of her mind, whereas the ‘false lover’ or the ‘non-lover’ is the one who regards only his ‘brutish passions’ toward a woman. The philosophical angle of her argument blends neatly into the religious angle. The woman in her religious retirement is meant to keep her heart fixed upon Christ, like so:

The true end of all our prayers and external observations is to work our minds into a truly Christian temper, to obtain for us the empire of our passions, and to reduce all irregular inclinations that so we may be as like God in purity, charity, and all his imitable excellencies as is consistent with the imperfection of a creature.The degree to which she disdains ‘wit’, ‘foppery’, external adornments, frivolous entertainments, expensive hobbies and fashions, and the degree to which she calls women instead to a life of contemplation and silence, a life of conquest of the passions (a term she uses more than once), away from bickering with each other and away from being so egregiously and unfairly mistreated and despised by men for their own ignorance (which is no fault of their own), is precisely a measure of the degree to which she is influenced by the elder Christian tradition and seeks after a form of askesis which recalls the work particularly of the Greek Church Fathers. After all, there is nothing more properly English than turning to the classical and post-classical Greeks for a good example. But she is no Puritan, by any stretch of the imagination! (As Sharon Jansen, the editor of the volume I’m currently reading, notes, the Puritans of her day were convinced misogynists from John Knox onward.) She is very much a believer that moral and spiritual regeneration comes out of a long process of contemplation and practice in which the woman’s will must coöperate with the Holy Ghost.

Mary Astell is indeed sensible that her religious retirement would be a temporary accommodation for most women, and she does expect that many of them would go back out into the world and marry. She believes, and argues forthrightly, that women who do so would still be greatly improved by education, and that having a firm religious observance and a mind enlightened by true wisdom would be a service both to her and to her husband, even if her husband is not so religious, well-educated or wise. On the other hand, she makes allowances for women who do not marry, and who choose either to stay among the religious as quasi-monastics, or else to go out into the world and be of service to other women as friends and spiritual advisers. This declaration that women may be independent of men and yet still have good standing within Church and society is where Astell begins showing certain glimmers of a more radical potential, as her later feminist commentators correctly note.

In both of these respects, Astell bears a strong resemblance to Ban Zhao. Ban’s Lessons for Women also hold forth both propositions: both that a well-educated woman makes a better and more virtuous wife, and also that a woman of virtue and education has a deep personal worth in her own right, and not merely as an auxiliary to a husband, a father or sons. In her own personal life as well, Ban Zhao demonstrates this: though she proved her worth as a scholar and historian by helping to compile the Book of Han 《漢書》 that her father Ban Biao 班彪 and brother Ban Gu 班固 had both put their hands to, and though she married and had children as was expected of her by the prevailing morals of the day, she went on in her widowhood to serve as a tutor, advisor and friend to Empress-Dowager Deng Sui 鄧綏. Her intellectual accomplishments and virtue far outweighed the expectations that Han society laid on her. (Insofar as Astell is a good Platonist – and she clearly is! – I dare hope she would not object overmuch to being thus favourably likened to a ‘virtuous pagan’ outside her own tradition.)

Astell can justly be claimed as a feminist, as Perry and Jansen both do, though I demur from the appellation of ‘foremother’ – more on that later. Jansen allies her Serious Proposal to the work of Italian-French proto-feminist Christine de Pizan, who also imagined quasi-sæcular women’s spaces for education and contemplation, and whose Boke of the Cyte of Ladyes had been translated into English a century and a half before. She certainly does not demur from challenging or spare the sensibilities of men who desire to keep women ignorant, or consider women as only ornamentations or outlets for their lust. But her feminism is of a kind that seeks to produce women who are wise and virtuous in the classical sense. She is very insistent that her aim is to better women’s character, and not to make of them cheap counterfeits of the other sex. Later feminists regard her work with a certain degree of ambiguity, as is probably justified.

At the same time – and this is speaking as a male reader, so take this with as many grains of salt as you like – it seems that her politically-conservative, Tory inclinations cannot be divorced easily from her insistence on the ontological, spiritual equality of men and women before God. Astell’s Platonic ‘forgetting the body’ allows her to claim for women a faculty for approaching the Divine – that ‘which is really yourself’ and ‘that particle of divinity within you’ – that requires no reference to men. It also allows her to claim through spiritual concentration a uniquely-feminine genius as a reflection of the Divine, one which is not merely pious and wise in a sexless way, but also ‘sweet’, ‘obliging’ and ‘amiable’. Through such claims Astell finds the means of fighting back the old Aristotelian bigotry that women are deformed men, which was still popular in her own day. And as we can see, Astell’s Platonism is very far from being apolitical; it supports what we may call a spiritual aristocracy in which women can fully partake, through this genius.